In the Jungle of the Cities: The Lost Children of New York

By Kathy Dobie

First appeared in The San Francisco Examiner Image, May 23, 1993

Come, we will go out into the world,” the children say to each other in fairy tales. They fly away, deeper and deeper into the forest. And when they have gone a very long way, they come to a little house where no one lives. “We can live here,” they say. And they gather moss and leaves to make a bed; nuts and berries to eat.

At 14, my childhood fantasy of flying, flying away, of nesting in the woods was hard shook by pavement under my feet that took forever to cross, by the hard-faced houses late at night, blinds drawn, rebuking lawns; the cop car that circled back. Running, running, but there was no woods, no nest, no tribe of children hiding in the trees, waiting to pull me up. There was the cop. Gray-haired and fat and not unkind. “Young lady …”

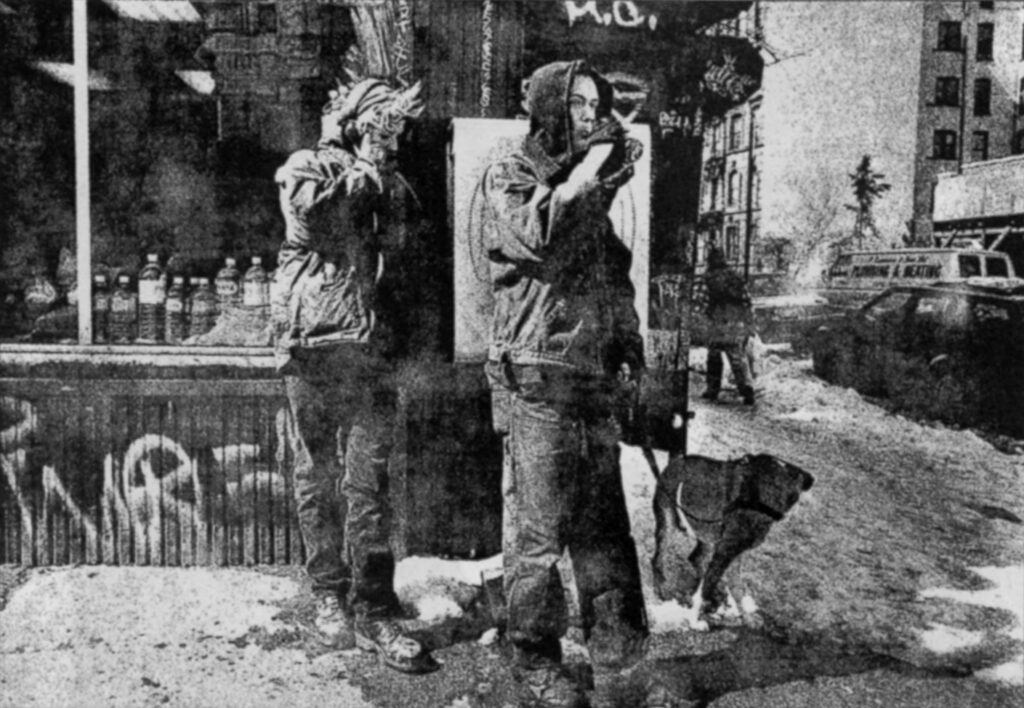

I found them almost 20 years later – my kids in the woods. Found them not hanging from tree limbs but doorways, calling “Spare change?”; pierced like pirates, rings in their noses and eyebrows, clothes hardpacked with dirt, their hair colored green and glued into spikes. They lived in abandoned buildings in the city, stole electricity for their space heaters and TVs. They were cocky and full of bravado. A gang of them would sprawl on the sidewalk, and though they begged for change, their pose was insolent. If they had already panhandled enough for beer and cigarettes, they would turn to insults. Cronus was on his second quart and getting surlier with each swallow when a college boy in a fat red windbreaker bounced by, a kangaroo in his brand new sneakers, his little pudgy ass perky in corduroys, looking so happy, so dumbly pleased with the wild East Village and his brand new freedom, that Cronus had to pounce. “Little Red Riding Hood!” he yelled.

Cronus left his mother’s North Carolina home at 13 – eight long years ago. I met him first on a winter’s evening, tucked back in a doorway on Avenue A in the East Village, calling out for change in his soft Southern voice. Then there were Peasant Rose and Dirtbag Mike; the lovers, Lydia and Slug. Kids from Boston and L.A., from Ohio and Connecticut. Most of them had left home at 13, 14 or 15.

I’d heard of squatters, of course. When I moved into the East Village in my teens, they were taking over abandoned buildings, hanging out signs: “This Property Belongs To The People.” They never interested me. That generation took over the buildings with their socialist rhetoric and then fixed them up in order to apply to the city for ownership. They worked toward legitimacy, moral authority, the center of things. But the squatter kids travel too much to homestead. They hop freight trains, mostly. Sometimes they hitch or take Greyhound, crisscrossing the country, staying at squats along the way. They dumpster-dive for food and clothes. They don’t call themselves runaways, nor would they say they’re homeless. The names they give themselves are“urban nomads,” “road warriors,” “travelers,” “urban Indians.”

That night, Cronus told pieces of his story, hunched over a bowl of sugared cereal and a quart of beer: Getting beat up by rednecks, skinheads and cops as he moved through the South. Locked up in juvenile hall. Practicing Satanism for protection and power. Eventually coming north. Meeting witches in the East Village; deciding that witches are wimps. His tale had all the violence and restlessness of our frontier past: brawls, jail, riding out of another town; the lonely dark and the rootlessness haunted by ghosts, by the Devil himself. At the end of the night I asked him where I would find him again. “In the breeze or the city morgue,” Cronus said airily. And I never saw him after that. Other kids picked up the narrative.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hey, F…!” A condom sails through the air and hits me on the shoulder. I look up to see redheaded Chad bouncing on his toes, blue eyes lit on me. The crooked spikes on his head (he uses glue in his hair) make him look like an angry cartoon character. He wants to be interviewed.

Chad can always be found on Avenue A, across from Tompkins Square Park. Since the park was closed, the kids meet here. On this block, the storeowners don’t chase them away, and the kids help them out when they can. In the evening, when the newspaper delivery trucks come, they carry the papers from the curb to the storefront. At night, they help carry the newspaper racks inside. The street life’s loose and raggedy enough to admit them, fast enough to interest them. A grizzled drunk calls over to Chad: “Looking good, my friend!” Chad shouts back: “You don’t have any friends!” And the drunk seems to take in the truth of this, and sinks dewy-eyed into his bottle. Chad says the only reason he doesn’t kill himself is because “I enjoy annoying people so much.” Chad won’t panhandle – he’s too angry, too proud for that.

He has his father’s blue-collar ethic; his father who works for the railroad in Chicago and kicked Chad out of the house when he was 15 because Chad wasn’t going to school, wasn’t working. “I deserved it,” Chad says. “I was a 15-year-old snotnosed brat.” Doesn’t matter anyway since he’s learned more living out here; already knew all the stuff they were teaching him in high school. The teachers said he was “learning disabled” when he was just bored. Now he knows sheetrocking, carpentry and plumbing by fixing up various squats. “Renting makes you stupid,” he says.

He grew up faster out here, he tells me, and then hastily corrects himself: “Not faster but sort of like ‘matured,’ but still a child at heart, still young.” Chad believes that other life — school, parents, then college, job — would have kept him green and made him old at the same time.

When he was 13, Chad was locked up for stealing a car. He doesn’t do that kind of stuff anymore; doesn’t want people to see him like that. He only tells me about it in order to defend his dad’s decision to kick him out. That was a long time ago — before he learned sheetrocking, before he made a commitment to his survival not as a high school kid living with mom and dad but as an “omnivore and a scavenger” on a poisoned, dying planet.

“You gotta admit the weather’s f…ed up. It’s pretty noticeable,” he says. It’s raining cold in late April. The water shoots down through a tattered sky, steams when it hits the street. “I think it’s gone too far. You seriously can’t save it. This land’s so toxic, you can’t tear down these buildings and farm this land.” Chad wears orange and yellow plaid pants that he’s cut off at his boot tops. Using rope, he’s sewn them close to his legs.

“Why should I dress in L.L. Bean and pullovers and loafer shoes — those things fall apart,” he says. “But my boots last forever. I love my leather jacket. I paint it, do fashion stuff with it, but it also keeps me warm and at the same time it’s good protection in a lot of stuff — falling, fights.” Their clothes are like a second skin; a thicker, tougher, warmer hide. They’re mutating to fit the environment. They say they’re “immune” to the cold after years of squatting. The dirt keeps them warm. In fact, showers hurt.

Five years from now, 10, if the world lasts, Chad could be anywhere on this wide Earth, he tells me. Living in the desert, a cave, “in f…ing Belize.” This summer he’s going to investigate an abandoned military base on Long Island, and some industrial wasteland in New Jersey. “I can survive anywhere,” he boasts, and his rough, happy confidence blows away the past, the Oprah Winfrey context, my readiness to grieve over the 15-year-old thrown out into the streets.

The squats lie east of the park in “Alphabet City,” where the neighborhood becomes Hispanic and poorer and there are many abandoned buildings and empty lots. The squatters have taken over some of those buildings; other residents have turned many of the lots into gardens. Small businesses line the avenues — laundromats, bodegas, car services. Drugs bring in traffic from the boroughs, New Jersey and Connecticut. The street life’s active but its language is Spanish and the squatter kids have no entrance. They’d rather hang out on Avenue A. The white girl with dirty face, dreads and American flag pants may be part of the swirl of Avenue A, but cross to Avenue B, then C, and the Puerto Rican men sitting outside the American Legion Hall regard her with hilarity or disgust. Occasionally, the neighborhood and the local politicians grumble about those middle-class-white-kids-from-the-suburbs taking over their buildings. Sometimes there’s a call to kick them out of the squats, to return the neighborhood to “the people.”

Some of the squats are gloomy, burntout places without electricity or plumbing, infested with rats and cats that shriek. The older, well-established squats like Umbrella and Life have work days, house meetings, rules and dues.

“C-squat” was opened three years ago by a 28-year-old anarchist from Texas named Bald Michael who was tired of the regulations in other squats. He broke into the building one night, using bolt cutters on the chained door. For the first few weeks, he and his “woman friend” slept on a pool table left behind, surrounded by rubble and puddles. “I consider that the birthing of C-squat,” he says.

A few months later, the kids started to arrive. More recently, C-squat’s been filled with refugees from two squats shut down by the housing police: “Tower,” which was inside the concrete base of the 59th Street Bridge, and “P.E.S.T.”, which stands for Planet Earth Scum Tribe. Twenty-three people live in C-squat now, most of them in their teens and early 20s.

It’s a five-story brick building, the back wall crumbled away. The windows facing Avenue C make a crazy patchwork – some boarded up, some broken, a plant in one, a wind chime hanging in another. On the metal grate that covers the storefront, someone’s spray-painted “HOME” and next to that, in a different scrawl, “ANGST.” The door’s usually locked; the kids wear their keys on shoelaces tied around their necks. Late in the afternoon, a girl with a splinter of bone through her nose carries plastic gallon jugs to the fire hydrant across the street, fills them, and disappears back inside the building.

The sun is bright and flies cluster at C-squat’s door, buzzing at the cracks around the frame. I step inside, the metal door clangs shut and the dark is moist and pungent. It’s the smell of piss bottles in the rooms, of many dogs, wet this and ripe that, and kids who refuse to bathe for weeks, even months, in spite of epidemics of scabies and lice.

All in all, dog heaven; right down to the dim and wavering light cast by red light bulbs. On the first floor, the cement-floored “community room” is plastered with graffiti: “I Am My Own Worst Enemy,” “Pain Is Isolation – And Isolation is the Absence of Truth,” “Demon Is The Nation,” “WAR – The Game Show.” Every inch covered with messages and pulsing red — like being inside the skull of a madman. “Tyrant and Dictator … Let Blood FALL upon you like Rain and let a Dying River of Severed eyes slide and flow over you staring at You endlessly.” Paintings of a fallen angel, a hanging man, a howling face.

There’s a hairy, slumping couch, a kitchen table, odd chairs, an upright piano with headless nude dolls propped up on the keys, collapsing piles of books, a drum set. In the back of the room is a refrigerator, cupboards, several hot plates. The shelves are piled high with blenders, coffee grinders, electric can openers — a rat’s nest of appliances laced with dust and cobwebs.

In the dumpsters of the city, the squatter kids find fruits, vegetables, day-old bread, worn furniture, broken stereos and TV sets. C-squat goes dumpster-diving every night but Saturday. They have the “vegan route” and hit the health food stores and vegetarian restaurants over in the West Village. Since they forage over a wide area, they go on bicycles. The food they bring back is shared. Some of the kids are on welfare; others panhandle on Avenue A for the extras — tampons and dog food, beer, tobacco and “other stimulations.”

“If squatting is anything, it’s the best argument for recycling,” says Peasant Rose. “We recycle buildings, we recycle food, we recycle clothes.” Her oily braids are arranged to cover her face. Brown eyes flicker behind them, surprisingly bold.

“I really believe highly intelligent people squat, not f…-ups,” she says in a sweet, piping voice. “Squatting is an alternative to killing your soul in order to have a place to live. If I get a 9 to 5 job, retire on a pension — to me that would be wasting my life!”

The next time I meet Rose, she no longer wants to be interviewed. She says she doesn’t want to get into “all that emotional stuff.” And so what do I know of Rose? That she slept under a bush by an L.A. freeway when she left home at 14, then squatted in Oakland? And two years ago, she and Dirtbag Mike hopped a freight train east and moved into C-squat? Not much; not enough to connect the dots. Oh, Rose cannot be explained, then; cannot be fleshed out by logic, by cause and effect. Rose must fly over us, piping her sweet song. And what could be the harm in that? Why should I insist that they trundle around their pasts, show me mom and dad?

I sit with her as she panhandles, her chiming, girlish voice and veil of braids and old mourner’s clothes proving irresistible to a biker hanging out with his buddies on Avenue A. He gives her a dollar, crouches near her, pets her dog, tries to tell her that he, too, had a hard time of it when he was young. Rose is imperious in her boredom. An old black man shuffles by with a small tree tied to the back of his head. He murmurs, “Yes-massuh, yesmassuh,” scrapes his feet robotlike over the sidewalk. The biker shakes his head sadly. “Crazy,” he remarks. Rose disagrees: “Oh, he’s the Tree Man – he’s a beautiful person!”

Rose will not live in the ugly world. She transforms the street into a parable — the leaves above the old man’s head are lit and tremble violently — but her flight from reality scares the squatter kid sitting next to her. He leaps to his feet and wraps his arms around himself tightly. Rose looks up at him with interest. He whispers that sometimes he’s afraid he’ll go mad. He wants to go back to the squat.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

As I walk around the squat making notes, the kids tease me. “Found any big, descriptive words yet?” they ask. “Enchanting,” one kid volunteers. “Festering,” another one says. Unintentionally, they’ve named the two poles my thoughts move between. One 17-year-old named Eris pokes his head through a hole in the wall (shaved bald, a silver ring pierced through his lower lip): “How about—‘Like living in a post-apocalyptic movie?’”

At the back of the kitchen, there’s an overflowing toilet; a circus of flies. The floor ends here, drops down to the basement, creating a cavernous space. The floor’s muddy and strewn with paper. The kids had plans to make this area into a performing space and open it up to the public but they were afraid the ceiling would collapse. So they borrowed scaffolding from another squat, found two I-beams at a construction site, carried them here (it took 20 kids to carry each beam) and installed one. It’s an amazing feat. The I-beams are huge; the scaffolding looks rickety. The other I-beam sits in the mud. It’s as if there was a flash of energy and light, work was accomplished, and then dark descended again. When I arrive at the squat in the spring, all construction has stopped. The kids spend a lot of time alone in their rooms. They sleep all day.

Walking up the stairs, the bannister’s slick and gaps in the floor have been covered unevenly with boards. Very few of the rooms have doors and many inner walls are missing, so at every landing, one sees cross beams, hanging cables, a whirling stack of clothes in the center of the room — more nest than bed.

When I ask the kids about privacy, they say they have more than enough of that. They talk instead of not wanting to be lonely, of being able to leave their rooms at any hour and find someone to be with — the virtue of 22 roommates. Lisa, a soft-voiced California girl with a bone in her nose, says: “I can be in my room and listen to people come in- I know everybody just by the sound of their footsteps.”

There’s one young squatter, named Pez, who installed a steel door on his room with bolts and locks. “That’s not common, but he needed an impregnable place,” Bald Michael says. For one full year, Pez never left the squat.

Michael took his door down, hung a shower curtain in the doorway, painted his three walls blue, nailed a worn Persian rug (a dumpster find) where the fourth wall would be, was once.

Almost every room has a space heater (they’ve pirated electricity from the street), though they make little difference in the winter. Michael has a stereo and a hot plate, too, and we drink coffee in his room. “I’ve got into raging fits and tore the room apart and left it in rubble for months,” he says cheerfully. Then he builds a smaller room and lives in there until he’s ready to make repairs.

Everyone here has wrecked the community room at least once, he tells me. He calls it “an expression of living … showing your totally pissed-off frustration, instead of some phony social decorum.” C-squatters are the target of much ridicule. To the other squatters, kicking in a wall is plain shit-where-you-eat stupidity. Those C-squatters are spoiled rich kids, the others gleefully insist. They’re manic-depressives, they’re “gloomy hippies” who think too much. But Eris tells me it’s not home if “I can’t go in a room and kick in walls.” It makes him feel safe. C-squat is the tolerant squat.

Michael’s the squat elder but he has no authority. He needs their hugs and their forgiveness as much as the rest of them. He got blind drunk last night and raged through the squat and the kids just trailed him and picked up the pieces. Today they joke with him about it.

In the community room, a mangled TV set is displayed on a shelf, its screen splintered and a bottle of Midnight Dragon Malt Liquor placed inside. That one was killed with an axe. A kid from New Orleans named Paul took a sledgehammer to another set. Peasant Rose disemboweled one, put a mannequin head inside and taped the words “TV LIES” on the cabinet. She hung it from the window in her room. Lisa likes to take apart television sets and make suits of armor out of the circuitry.

For the way it babbles on and on regardless of them, for its shivering, delighted voyeurism, its naive view of the world, its middle-aged morality, TV has been condemned to a punishment that never ends, using the one language TV understands the best. A stupid commercial, another breathless exposé, one more valentine to law and order — and a squat kid will up and axe the screen in. “If somebody wants to watch TV later, they can get another one easily,” Lisa says. They just go dumpster-diving.

Most haunting are the wooden boxes some of the kids have built to sleep in — smaller than Michael’s small room, about the size of a wardrobe, the entrance hung with black or green plastic, like garbage bags.

Sean built one in the middle of his living space on the third floor. On the plastic sheet covering the door Sean’s written: “PAIN DOG RESIDES HERE.” An arrow points down: “WINTER WOMB FOR WARMTH.” When it’s cold, when they don’t want to sleep in those open spaces, when they need to tuck themselves away for a while, they sleep in these gloomy cabinets.

Michael had plans to move out and get an apartment and a job. He’d healed himself here in the squat, he told me; he was ready for the big, bad world. But then he changed his mind. “I decided to be a welfare artist for a while,” he says — to pick up his check and paint. Michael seems to be in continuous preparation for some big step — taking his art seriously, moving back into his room, walking out into the world without fear. He describes his “internal work” in great detail; talks of a time last spring when he made a “major breakthrough as a person”. It hurts to listen to him. He seems to be sketching maps of meaning over inexplicable suffering. As we walk around the squat, I’m thinking about a life narrowed down, shunt off to a side track, a tangent; of the lies you tell yourself about wanting to live in this smaller place.

And then I fall through the floor of the squat — one leg, up to my thigh — and I’m shaken from my frigid imaginings. Michael helps me out. We laugh happily. He’s so used to those holes he forgot to tell me about them. In that moment, I’m taken into C-squat, I feel its benediction — there is nothing I could do, nothing that could happen to me here that would be cause for shame or ridicule. The long cut on my calf, the throb deliver me from the cruelty, the melancholy judgment of the ghost-narrator.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

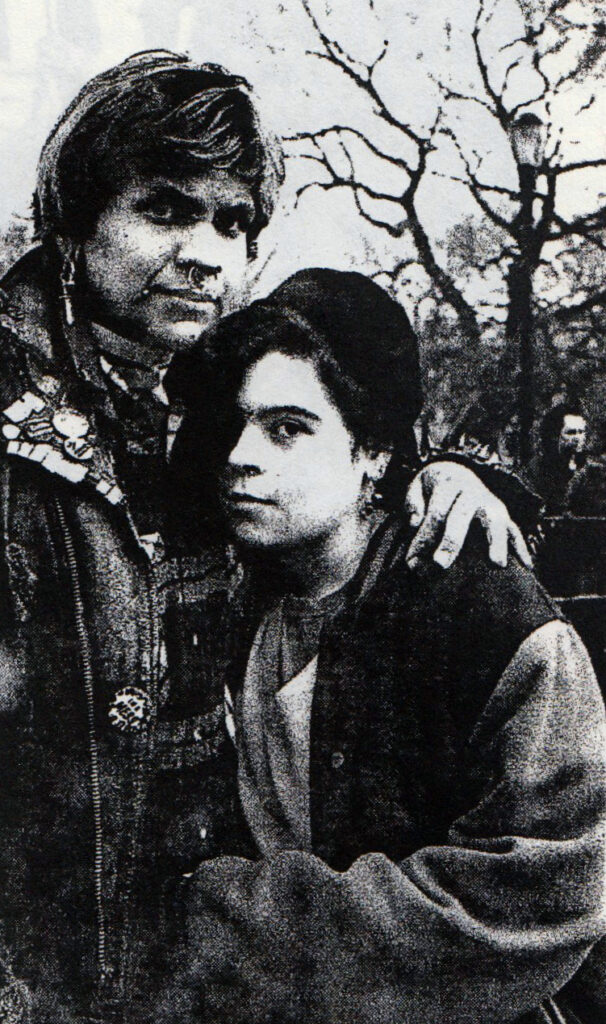

Slug and Lydia saunter down Avenue A. Lydia carries a cane and thumps the sidewalk heavily, irregularly. Slug pulls at the two thick rings in his nose. The lovers do not touch but match their pace — slow, deliberate, beat out with the cane, almost regal. Slug, brown-skinned, glossy-haired, wears a bolt in one earlobe, a gold loop through his lower lip, and a small ball and stud stuck through the middle of his tongue.

They’re heavy with clothes — tattered animal hides, thick with dirt and wear. Slug has painted one sleeve of his leather jacket green, sewn leopard skin on the cuff, zebra skin on the pocket flaps and strung a piece of barbed wire across the left breast. On the back of his jacket, he’s safety-pinned a patch of plaid cloth and the words “Chaotic Discord.” Lydia, short and chubby, wears a beret, many jackets, a tiny skirt, garters and black stockings. They are like nomadic warriors, draped with the spoils of battle. “Here comes the granddaddy of punk!” one of the squatters announces happily.

It’s Slug who grows old. Slug who carries his past with him, who squints at the future, sees nothing and is afraid. Unlike the other kids, he speaks openly about his childhood, but not out of any sense of resolve. He hasn’t triumphed over anything. Squatting hasn’t absolved the past.

“It’s just surviving. You don’t fit into this world so you make your own society, you survive the world,” he says.

Slug has worry printed so deep in his eyes that even nose rings and studded leather and pierced tongue can’t hide it. “Even living with my parents, I felt I didn’t belong there … I felt like I had nowhere at all. I thought: ‘What’s gonna wind up with my life? Just be an older bum on the streets? You don’t know what could happen. Society’s pretty scary. It really is.”

When Slug tells me he tried to kill himself at 13, he’s not “confessing.” It becomes easier, then, to ask him why. “Ever since I was a young kid — 6 or so — there was something about me, nobody accepted me. I didn’t have friends. I couldn’t deal with it.”

But ask him where he got his name and he brightens immediately. In grade school, a girl called him a “slug” — and that was when he “looked normal and everything.” He liked it — “Yeah!” he cheers, tongue unrolling, gold glittering. “It’s my personality – slimy, ugly, and everybody f-s with you. Everybody, when they see a slug, their first intention is to put salt on it and kill it. And the first intention when people see me is to want to hurt me.”

His family split up when he was 13. His father was involved in the drug business and some rivals were gunning for the family. Slug’s parents told him he should try to make it in the world on his own. His mother flew to South America, his father seemed to vanish into thin air.

For a while, Slug lived in the parking garage of the New Haven Coliseum in Connecticut, and continued to attend school. Then he hitched a ride to New York and moved into ABC squat with a group of punk rocker kids — “We were all urban f…-ups,” he says wistfully. Those were the two best years of his life — because he belonged, because it’s the longest he’s lived anywhere. ABC was closed down by the housing police, and the kids scattered to the streets. He’s lived in many squats since then.

Lydia’s pregnancy scared Slug. “I was shocked. Scared, too. Before, I wouldn’t have been — I had my home. I had my friends.” He and Lydia applied for welfare — they’ll get $210 a month for an apartment. “We could open up our own squat but with all the cops and shit — you can’t live like that when you know you’re gonna have a child,” Slug says. “You can’t risk that the cops are gonna come and bust you over the head with a kid inside of you.” He dreams of traveling to Europe and squatting there. “I hope things are gonna turn around for me in the next life,” he says with such simple gravity I have to catch my breath.

Here and there on Avenue A you see the kids who haven’t been taken in yet. New arrivals in town. Or rejects. The kid with the clean face and contacts and green hair that’s too evenly, newly green, like a hat he just bought and now he waits anxiously under it. When he sidles near the gang, they ignore him. He hangs there unhappily. “Summer-campers” they’re called, after a punk rock song. Kids in from the suburbs, looking for a summer adventure. They won’t be here when school starts; certainly not when the winter winds begin to blow. “Poser punks” who bring offerings — boots, clothes, mom and dad’s money. The squat kids take it all, and walk away. They hate them because they’re not in it for the long haul, because they’re dumb and weak and eager, and dangerous. They carry with them the stink of another reality — of homes and lives that are worth returning to.

The kids are continually forming and reforming themselves around different enemies. A few summers ago, skinheads used to stomp through the East Village, looking for heads to bash. One July 4, they marched into Tompkins Square, waving an American flag like bullfighters. The squatter kids burned a flag in reply and a battle ensued, raging up and down the avenues surrounding the park. It was a lot of fun and the squatter kids were united then. This year, their tribal identity seems to hinge on internal divisions — chaotic punks vs. peace punks, omnivores vs.vegans, drunks vs. monks, the dirty vs. the downright filthy, otherwise known as the “crusties.”

The chaotic punks, like Chad and Slug, dress for war and toxic rain; the “crusties” for flight and penance. They wear dirt and rags: Peasant Rose with her oily veil, Dirtbag Mike moving in his own dust storm, eyes glowing angrily from his dirty face. Kicked out of his parents’ house at 13, locked up in juvenile hall for three years, Dirtbag’s still as small as a child. His beard is pulled into a short stiff ponytail, like a finger jabbing the air. His friend Sean, long, lithe and blonde, wears a candy-striped dress, like a housewife’s shift, over his T-shirts and jeans.

I met Dirtbag and Sean at Daffodil Cafe, a tiny Ukrainian restaurant a few blocks from the squat. Daffodil doesn’t do much business, the kids feel comfortable there and coffee refills are free. “It’s our kitchen,” they say of Daffodil. Indeed it seems to be: Before they leave, they clear every coffee cup, spoon and crumpled napkin off the table and carry them over to the counter.

You’d think the waitress would adopt them—such good kids! — but instead she serves them impassively. Her real feelings show when her friends arrive and they begin speaking Russian, pointing their chins at the kids and laughing hard. One afternoon, after the floors had been mopped and the tables washed down, a group of kids came into Daffodil, took one whiff and shouted: “Phew! This place stinks!”

“You’re so ug-ly, you’re so ug-ly, ug-ly inside,” Sean and Dirtbag are making up lyrics to the Billy Joel song playing on Daffodils radio. Growling them at each other. And then — did I blink? — Sean is kneeling on the ground, his head on Dirtbag’s breast. Dirtbag is holding him.

Sean and Dirtbag have a band called Dedeth and they invite me to a performance. Sean says his mom will be there, and his dad won’t. He almost wishes his dad would show up, Sean says, because if

he did, Sean would stand up on stage and yell: “Go ahead, dad! Bash my head against the wall now!” Then he would motion to the room full of squatter kids and tell his father: “These are my brothers and sisters!”

And I imagine dad going down and disappearing in a dust storm. When it clears, they’re wearing his shredded clothes.

Inside the Living Theatre, we sit on bleachers and squat bands take the stage. The bass is cranked up and the two guitars sound like cars crashing in slow, terrible motion. The drums also sound metallic; it’s like a junkyard playing itself. Music fit for scavengers. The squatters dance — without partners, but not alone. Two boys bump into each other and slide away. One sinks to his knees and the other finds him and pretends to fall over him. They roll on the ground and get up, flushed and uncertain. They lift the singer and trundle him — awkwardly, carefully — around the floor.

Crash, crash, bang, crash; heavy, bloody beat, slightly off-kilter, accent on the deformed limb. The squatters stand in a circle breathing hard waiting for some notion, some emotion to move their limbs and make the plunge into that empty circle, that public space, all alone. Finally, some kids are pushed in, and they hop around helplessly until someone else is pushed out after them. To cut through the frigid space, to be folded and tumbled in flesh and breath …

At the theater, Sean introduces me to his mom, a blonde woman with haggard face and watery blue eyes. She’s moving to a Buddhist community in Vermont. She’s glad I’m writing about the squatters. “These kids need some attention,” she says.

NO DRUGS” written big on the hallway door. In most squats, violence, stealing and white powder drug use will get you evicted. Coke, crack and dope are trouble because they make thieves, because they bring drug dealers into a squat, because users become too self-involved. But the “NO DRUGS” sign is more aspiration than rule. A number of the kids at C-squat have become addicted to dope. Dirtbag, Pez and some of the others are going to hitchhike to an abandoned cabin in Vermont so one of the kids can kick his habit. It’s easier to kick in the woods than in the drug market of Alphabet City, they say. From there, they’ll hop freight trains west.

It’s the beginning of the Great Migration that takes place every summer. The New York squatters head west; the West Coast squatters come into New York. C-squat is a “living entity,” I’m told. It will survive their comings and goings.

Many of the squatters will travel to an anarchist gathering in Ohio, and then on to the Rainbow Family gathering in Colorado. During the year, they hit Grateful Dead concerts, Mardi Gras — every big family picnic in the country.

With scorn, they describe The Rainbow Family Gathering as “a bunch of hippies dosing in the woods.” A bunch of old hippies. Still they go. To have a destination. To meet with their elders. To give them grief. Lisa says that at the last Gathering, the squatter kids were the “bad vibes camp.” She describes the hippies screaming: “We love you!” and the kids screaming right back: “We hate you!”

“It kept a good edge to it,” Lisa says calmly. “Kept everybody from just lying around in a big pile and hugging.”

Lydia and Slug won’t go this year. Lydia’s given up sniffing dope and drinking but not smoking cigarettes. She asks me for one and Slug watches her. “You’ve been smoking a lot today.”

“Nah! This is only my second one,” she insists. Slug disagrees. They toss proof back and forth until Slug says, “Anyway, don’t smoke this whole one.” Lydia makes a face. “Really. Put it out after this drag,” he says, his forehead knotted with distress. “The kid’s probably having an asthma attack right now.” Lydia laughs but kills the cigarette. When she bitches about how hard this is, Slug says, “Yeah, but at least you have something to live for.” Lydia opens her eyes wide at him: “You too!” He really wishes he could be the one who’s pregnant — “I have a lot more willpower than she does.”

Last week, Slug brought Lydia to a restaurant. She ate, he didn’t. “Why not?” I ask him. “I didn’t have enough money,” he says to me, and Lydia’s shocked. “You said you weren’t hungry!” And the immensity of his gift — the revised scenario — hits her hard and she grins ear-to-ear, bumps against him, rubs his back and jostles him again.

Lydia was raised in Boston — her father’s an electrical engineer, her mom owns a small business, her older brother’s an auxiliary cop. She wasn’t a “normal kid,” she says. A normal kid would have been returned home by the cops after running away. Lydia — who was 14 when she left home — was put into a mental institution. She doesn’t know why; doesn’t understand at all. Remembers there was a judge, but not the decree.

In fact, most of her childhood memories have been wiped out, except for those of her brother’s big feet pounding up the stairs after her, kicking in her bedroom door when she hid there, beating her up. One time he handcuffed her first. Lydia says her dad’s mild-mannered, wouldn’t hurt a fly, says her mom and dad love her a lot. I can’t help but see a ’50s TV family: He with a pipe, she with an pink-and-white checked apron, wondering aloud why the kids are making such a racket upstairs.

When Lydia left home, I imagine that her parents couldn’t help but feel relief. She tried to return once, but her brother stuck his foot in the door and wouldn’t let her inside. “My family and I get along fine as long as I’m not around,” Lydia says, without any irony, any bitterness at all.

She tries to keep in contact with her parents, she says, so she can borrow money in an emergency. She and a lot of the kids return home for the holidays. I imagine their parents are happy to see them come and as happy to see them go. More refugees than runaways, my kids in the woods. A lot of them just walked out the door – mom packed a lunch. Or the family self-destructed, and they fled the disaster scene.

They defend their families against my judgments. When Spot decided to leave home at 15, his mother drove him the 30 miles to Portland where he would begin his new life. When I question her behavior, Spot gets angry: “I think it was very much in the spirit of family — living together wasn’t working out. I don’t think the family’s broken up — family’s a weird concept, anyway — it was just obvious we weren’t able to live together happily or healthily.”

Though Cronus hadn’t seen his mother since he was 13, he told me with warm force: “My mother loves me.” This is mother’s love as mantra, lucky piece, plastic virgin on the dashboard.

Only when I ask will the kids mention the father who beat them up or the alcoholic mother who kicked them out. One boy said shyly: “I don’t know any girls who weren’t abused when they were kids.” They talk warily of their parents’ unhappiness, the divorces, mom’s new boyfriend, dad’s girlfriend. They pull back then: “But don’t put that in your article.” They don’t want to be described as runaways or refugees; to be seen as messed-up kids. They want to escape the context of family. And, ay!, I drag them down.

“There’s no family life really,” Spike says. “Sometimes I wish there was one …” And he hangs there, mouth open, stuck in a regret that opens endlessly, until he jerks himself back with the bitter complaint: “They couldn’t even keep their relationship together!” They feel the burden they are to their families keenly. It terrifies them — if not this, then what? “Where Is My Home?” is scrawled on a wall in C-squat.

“Wake Me Up When It’s Over” is also written on the wall — and their “sleep” is dope and the little black cabinets. Tuck in, tuck in — for there’s no fear like the fear that you may have no place in this life, you may not be fit for living. “Screamingly scared of the world,” is how Bald Michael describes it.

So they depend on no one. Their dependency is on the group; their responsibility and loyalty to the ever-changing tribe. As they travel across the country, “there’s some people dropping out, some people joining but the group will stay,” says Eris. It’s an ingenious solution to the nuclear family fallout. “We don’t have much more than each other — nothing else is permanent,” he explains. “My deal on it is tribalism. We have our little pack and we take care of each other.”

Individual loves and friendships come and go; they are not encouraged, longed for, enshrined. They’re not heading toward “my one and only love.” They think it’s important to leave when the feeling’s gone. They trumpet this. They travel in groups — not just across the country, but over to Avenue A. Five is better than two; a nation of squatters the best of all.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

First sunny day and Chad has his sunglasses on — a jagged hole in one lens and behind it one bold, authoritative blue eye. Bouncing up and down on the curb, he lectures me on the History of the World. When he was kicked out of his parents’ home at 15, Chad spent a lot of time reading and sleeping at the University of Chicago library. His knowledge seems to have come to him less from studying those books, than the books releasing their images — flashes of fire, blood — after he rolled into sleep, a ragtag boy in the repository.

“You can tell a lot about people by how they think about death. The Egyptians — who kept slaves and treated people like dogs — buried their dead with gold and shit, so they could pay their way into heaven,” he says, the brightened blue fixed on me, his gaze both bold and embarrassed, as if high feeling always carries Chad over the edge of his own social ease. “But in Celtic mythology, you couldn’t enter Valhalla without having a saga. That’s why they fought and pillaged and burned and wandered all over Europe — to get a saga.”

Chad tells me an improbable, funny tale about the last Rainbow Gathering. He dropped acid and got into a fight with a hippie about whether or not Chad had “bad energy.” Chad beat the hippie with a log. Then Chad went into the woods, caught a rabbit with his bare hands, brought it into the vegetarian’s camp, killed it and skinned it in front of them. “This is living with nature,” he told them. As the hippies formed a “healing circle” around him and began to hum, Chad growled: “Heal yourselves!” and used their campfire to cook his rabbit.

A folk tale for the road warriors. And that’s why the squatter kids say they travel — to collect stories, to make their saga.

“I talk to older folks, people’s grandparents and they have two or three stories to tell,” says Lisa. “They sum up their whole life with these stories and I don’t want that.” Peasant Rose proclaims: “I want to travel all over the world! I want to have stories to tell my grandchildren.”

Not their real life stories, no. They want to write themselves into some glorious adventure. Eris boasts: “You watch movies about things that happen to us all the time. Ferris Bueller’s Day Off — people say that’s a great movie, but why not just go and do it? Or books about jumping trains or all the post-apocalyptic movies about bands of kids running around — we’re doing it!”

Before Pez left on his journey west, he wrote on the squat wall: “This Is The Beginning The End Of It All.” A call to the muse if I ever heard one; boosting the life into mythology. I’d like to let them fly out and away, across the country and into the metaphor- urban Indians. But I feel constrained by their pain — the boxes, the Ibeam in the mud, the dope addiction, the evidence of a hard struggle to keep themselves intact. Can I describe their suffering without condemning them to it? Can we see them as more than the sum of their injuries? It’s the question of a writer, and perhaps of an adult not entirely comfortable with being one. Once I flew out into the fairy tale and now, like the fat, grayhaired cop, I circle back, lights flashing “Danger!”; heavy with concern.

Outside C-squat, a Martinson coffee can holds white flowers. Unlike most street memorials to the dead, there’s no name, no date, no message of luck or longing to the departed one. Paul, the 20-year-old from New Orleans, overdosed and died in the squat one weekend in April. When the kids found him in his room, he was already blue. They tried to get him breathing again. One kid ran out to call an ambulance; another to get Paul’s girlfriend, Killjoy. The others carried him down to the community room where he died before help arrived. A candle burns inside a milk crate marking the spot where he lay. “The house is haunted now,” says Peasant Rose from deep beneath her braids. And suddenly, everyone’s leaving on their summer odyssey early.

The kids don’t want to talk about Paul except to say that his death “just gave everybody a kick in the ass to go.” They talk about how long it took the meat wagon to show up — seven hours! — and how the cops on body watch stood there and made jokes. “It was just so disrespectful,” Lisa says.

Last winter, Bald Michael suddenly realized that half the squat was on dope. He felt sad but he understood: “For whatever the reason the squat wasn’t enough anymore.” The kids decided Paul wanted to die. “But he didn’t,” Michael says. “He wanted to stop the pain.”

They say they want to travel all over the world — but “place” isn’t important, mobility is. When Paul died, they had to flee. Squatting is about saving lives, about doing better than family, about surviving the cold world. They say: “We’re tighter than family because we keep each other alive.” They say: “Once you’re here, you’re not the really ugly person, the screwed-up kid anymore.” And then Paul died in their arms. Imagine the terror.

If not this, then …?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

At the end of August, most of the kids have returned. C-squat has a new energy. They’re building a room on the fourth floor – rubble raining down into the basement with every hammer blow. Dirtbag Mike plays his drums in the community room with such fierce intensity it comes close to joy. They’ve decided to turn that room into a performing space. They’re going to paint the walls plain white. They’ll call it “Spooge Cafe” — “spooge” being the term they’ve coined for the rotting food they find in dumpsters. A new kid lives in Paul’s room–he’s hung little plastic bats from the ceiling of the box. They dangle in the darkness there.

Peasant Rose and Pez are still out there somewhere. Chad’s spending a lot of time alone, one of the kids tells me, writing songs for his band, Humyn Sewage. Cronus has been swallowed up by the street. Spike explains: “First he was Cronus, then he was Coke-us, then Crack-us …” And then he was gone.

Slug and Lydia have moved to a new squat. I see Slug for a minute on the Avenue. He looks bedraggled. He’s colored his hair in rainbow stripes. Underneath, his forehead is stamped clear through with worry.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~