Long Day’s Journey Into White

Skinhead Girls, USA

By Kathy Dobie, photographs by James Hamilton

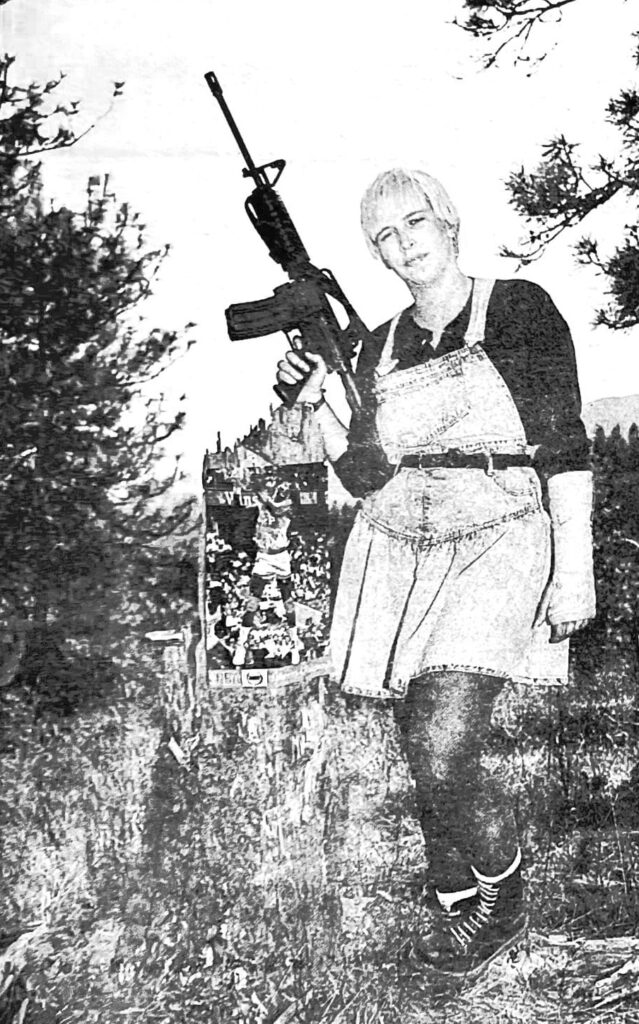

I MET HER IN A San Francisco bar—a big, straw-blond girl with a baseball cap jerked bac\r head, wearing a flight jacket and red braces, her blue eyes lined in black. Looking like the girl who crashed the boys’ clubhouse. Liz B. is a white power skinhead, a recruiter for the American Front, a self-described “white supremacist feminist”—and the most self-assured 22-year-old I’ve ever met. “Liz?” I ask the big blond sitting in the empty bar. “Kathy,” she states. “I picked you out outside. I saw you in the car—you were gulping down your coffee and then you threw the cup over your shoulder into the backseat. I said, “That’s her. That’s New York.’” Her voice is slightly clotted and so soft it’s almost a murmur. It makes everything Liz says, even the most outrageous comment, sound offhand.

At that first meeting, Liz and I decided to take a trip through skinhead territory. We’d start in San Francisco—she’d introduce me to the small, die-hard band of skinhead guys still there. Then we’d drive up to Portland and meet with skingirls from the American Front-one of the best-organized skinhead groups, with members across the United States. After Portland, we’d head over to a whites-only compound in Hayden Lake, Idaho, to meet Christian. Identity skins-skinheads who’ve found religion and a community of elders in the white supremacists of the Aryan Nations church.

The boys in San Francisco wanted to come on the road trip with us. Liz told them no: “It’s girls only. It’s Thelma and Louise.” She packed her tapes of white power music for the drive—and Harry Connick Jr. She brought her “survival pack”—two weeks’ worth of navy-issued food rations, canned water, and first aid supplies—just in case. We cut across the Bay Bridge at sunset, Liz murmuring beside me that the feds were certainly already alerted to her travel plans. That’s how our road trip began, though mine had begun that first afternoon in San Francisco—a long day’s journey into white.

Liz B. is the last skingirl in San Francisco. It’s just her and about nine skinhead men. The city has not been hospitable. At American Front’s last demonstration, 13 skinheads were met by more than 200 counter-demonstrators throwing sticks and bottles. From an Associated Press story: “ ‘White Power, White Power,’ a large, blond female in their ranks shouted through a bullhorn as items rained down.” That was Liz. Bob Heick, the founder and director of American Front, was hit on the head with a battery and he began to bleed copiously. (In the many photos the skinheads took of bleeding Bob, he looks dazed, sacrificial.) The cops had to cart the skins away for their own protection. American Front moved its headquarters to Portland.

The younger skins in particular are a transient group. Their uniform-shaved heads, flight jackets, Doc Martens with red or white laces (one signifying neo-Nazi, the other White Power)-makes them visible to each other; makes a community out of ideology. They’ve made their white skin a flag, a threat, a target, and a badge of membership. In their mythology they’re the street warriors of the Aryan race, and therefore, sometimes, its martyrs.

Liz comes from a very rich California family (her parents divorced when she was six). She grew up on a ranch, saw her first black person on TV-thought the person was in costume, she says. She was introduced to the White Power movement when she was 13 and attending boarding school in Colorado. In town, Liz befriended two brothers, the sons of Klan members. She found their lifestyle and beliefs exciting. “I saw it as an adventure, as opposed to the Volvo-driven, suburban family lifestyle.” At 15 Liz got her “fringe” (the girls shave the middle of their heads and leave the hair long on the sides) and got “jumped in” to the movement-beat up by the other skinhead girls, as was the custom at the time. Now, only boys get jumped in, and only some of them at that.

For a while, Liz studied photography at the Art Institute of Chicago. “I wasn’t dealing with oppressed people—with minorities and homosexuals. I was depicting upperclass people, traditional families, Klansmen and women, Nazi skinheads.” She adds unnecessarily—“Definitely not popular in art school.” From the art institute, she went to study at Oxford but was deported from England a few months later for associating with racists. She’s been photographed so many times by cops and gang task force members that Liz and her friends joke about the cops trading their photos like baseball cards—“I’ll give you a B. and a Heick for one Metzger.” “They consider the right wing so much more dangerous than the left,” Liz says. “There was a demonstration here in San Francisco outside the recruiting office. The communists and fags were dragging out the office furniture. If those were right-wing demonstrators, anti-abortionists, or Ku Klux Klan, the whole National Guard would be out. But I don’t think the government takes the left seriously. They don’t have to—they’re always tripping themselves up. They’re a bunch of wishy-washy granola-munchers.”

The skinheads believe that most whites are racist, and that skins are just braver than most whites. “Skins wear their beliefs,” they boast. From their point of view, they’re attacked on the street, hounded by the government and the media because of their political beliefs. Or as a 19-year-old skinhead named Steve says, referring to George Orwell’s 1984—“I consider myself a thought criminal.”

Steve thinks the city is sick—all the nonwhites, all the homosexuals—and is abusing every bit of it. He wears handcuffs on his belt loop in case he meets a willing girl; he fights, drinks in death-rock clubs, goes to art films with Liz (his favorite is Breathless); he dresses in a trench coat and boots (no pants) for porn movies, in an executioner’s hood for a night on the town, adopts a “militant gentleman’s look” for a TV interview on hate crimes. “San Francisco is still a free-for-all in spite of all the leftwingers and p.c. people,” he says.

Liz listens to N.W.A—“they’re our counterpart.” While visiting her mother she reads Dickens, and her mom’s taken aback. “She thinks I only read Mein Kampf,” Liz says, too amused and in control to be sarcastic. Liz takes occasional “trips” into the mainstream-art school, the day-care center where she volunteers, and where most of the kids are nonwhite. I think she wants to see if she can survive there. She doesn’t dress as a skinhead and neither does Steve on his job. Their hidden identities give them power. When Steve waits on a customer he thinks, “If only you knew who was serving your coffee!”

Steve grew up in an all-white, rural town in Maine. He was a loner, a book reader. He first heard about skinheads in a Rolling Stone article. What Steve remembers from the piece is a moment when the reporter admitted being afraid. It must’ve turned a lot of white kids on-cool, this is for me!– because they joined in droves after the story came out. Liz calls them “new school” – skins—“they have more of a gang mentality,” she says, and the older skins feel they have to educate them.

“I believe in the propagation and protection of my own kind,” Steve announces. “That comes down to sex and violence—which we’re so out of touch with.” He’s against “race-mixing,” homosexuality, and abortion. He’s rather mainstream at that. His life is full of exceptions to his avowed philosophy. “My last boss, Chris, was openly gay,” Steve tells me. “A punk rocker who worked there told Chris: ‘Do you know what you hired?’ Even though Chris knew, he and I… well, I wouldn’t say I respect him but I got to like to talk to him because he’s intelligent. I respect intelligence. I’m sure he talked shit about me to his boyfriend, just like I talked shit about him to my friends.”

Tonight, Steve’s pleased with himself because he and some skins joined a local protest against the Man-Boy Love Association. When the skinheads arrived, the TV cameras headed straight for them. Steve thinks they got good publicity for the movement. I think the media was delighted to make a connection between conservative political types and neo-Nazi skinheads. When skinheads join anti-abortion rallies, the TV cameras love them there, too.

Steve has a loud voice. A vigorous, enthused delivery. I can see the odd duck he must’ve been in high school. Unknown to him, the white couple drinking next to us in the bar have noted his skinhead dress and have been smiling smugly at each other during Steve’s various pronouncements. They’re in their early forties. She wears corporate dress; he has longish hair, wears a leather jacket and pleated, nubby pants—a professor perhaps? I hear her say to him: “Why would anyone be interested in them?” When Steve leaves the table, the man raises his eyebrows at me and my notebook-a conspiratorial gesture I ignore.

When Steve returns, the white couple leaves and I tell him about them. He looks hurt. He thinks it’s hard to fight for “kinfolk” who don’t want him to fight for them. He says: “In the Viking days, the warriors would come home after sacking a village and they’d be welcomed, some buxom women serving them ale … instead, I get bottles thrown at me and called ‘scum.’”

While he’s hurt that the couple rejected him, I just can’t see what these white folks are so smug about. Fear or hatred, I’d understand; curiosity or deep discomfort, even more so—but smugness? Isn’t it a little easy to feel better than neo-Nazi skinheads? Do they think these white teens appeared out of thin air? When Steve says most whites don’t know their own attitudes about race, I agree, but would add that they refuse to know. Just find the right set of attitudes and language and slide by with that. I remember a college professor of mine addressing the class one day with the simple question: “Who hangs out in the corridors that connect the college buildings?” And the class froze. The answer was plain: the black students. But we wouldn’t even speak the evidence of our senses for fear it might be construed as racist; for fear of where he was leading us-into what abandoned corners of our hearts.

Like most of the skinheads I meet, Steve knows that it’s this anxious silence, this guilty carefulness of whites that he’s provoking. “I don’t have any trouble from younger blacks,” Steve says. “They see me and say: ‘Oh, he’s down with being white.’ It’s white people who have to prove they’re not racist—they’re the ones who go out of their way to attack me.”

For the most part, the media has set the skinheads at a safe distance by portraying them as goose-stepping robots, or by inventing some simple psychology that explains them away (as I’d like to do). As one skinhead tells me: “They say, ‘They all come from broken homes and that’s why they became skinheads.’ That’s partially true. Not that we didn’t have these racist feelings beforehand, but now we belong to something. We do have family.” Still, the skinheads hate this explanation: “It’s almost like saying we’re white trash. We’re all from poor families, we all had such sad childhoods—so we decided to get together and beat people up.” As Liz notes: “To see us just as a street gang makes us seem less dangerous.”

That night I meet Liz’s boyfriend, Kiwi, and his roommate, Gordon. They’re both unemployed, restless, at loose ends. Kiwi’s a tall, loose-boned New Zealander with brightly lit eyes—he seems ready, always ready for … some explosive fun. But those eyes can suddenly burn with anxiety when he looks at Liz. Gordon has the same aim less energy rolling off him—but it’s angrier. Both guys can turn on the most solicitous, gentlemanly manner—they seem to want to throw down capes and protect someone or something.

Kiwi and Gordon share an apartment with three college kids. The kind of people the skinheads call “generic whites”—whites without any acknowledged race-consciousness, the supposedly “color-blind.” The two girls linger around Gordon, Kiwi, and Liz, soaking up their energy, trying hard to get their attention; half afraid of it, too. With studied blandness, one girl, a poet and college student, tells the room in general: “Tonight at the bus stop, some black guy shoved me…”

The skinheads pay her no mind. Another girl comes into the living room with her guitar—flutters near the doorway. Liz looks at her and says dryly: “Kumbaya.” Gordon suggests she play a tune. The girl laughs unhappily and leaves. Their male roommate never comes out of his room. I see a Greenpeace sticker on his door and hear Paul Simon’s “Graceland” coming from inside.

Most of the San Francisco skins are street—“I was out on my own when I was 14, 15 years old,” Gordon says. “I’ve been in and out of jail constantly. I’ve seen people killed. A lot of people like these pseudo-intellectual assholes, these total closet suburbanite kids, the only black people they’ve ever seen is on TV… they haven’t seen what goes on behind the curtain. They think we’re wrong because it’s cool to think we’re wrong.” He says that when he first became a skinhead, the other kids dug it—’cool, you’re a rebel.’ “Now it’s—’oh, you’re a fucking nut!’”

They refuse to belong to any of the organized skinhead groups like American Front or White Aryan Resistance (WAR), or to even give themselves gang names like the Hammerskins in Texas, or East Side White Pride in Portland—“That shit is for kids. It’s an identity crisis thing,” Gordon says. They’re still into the “fight and fuck lifestyle.” Still visible skins—“flight jackets and Doc Martens—they get attacked a lot. “Ah-I see your lifestyle finally caught up to you,” a cop told one skinhead shot in the stomach by a black gang member.

That evening Gordon shaves Kiwi’s head, and then announces that he carved “Crip” on the back. He and Kiwi throw other possibilities back and forth: “Blood,” “Word,” “Homeboy.” These city skins perform a ritual that Liz calls “a rite of passage into manhood”-running through a black housing project at night yelling “White Power!” It’s something I imagine a lot of suburban white boys can relate to-testing their manhood against the media’s icon of the Uzi-toting, violence-loving, fearless black youth.

A few blocks from Kiwi’s apartment, there’s a 19-year-old girl who’s dated some of the skinhead men and calls herself a skinhead but the boys call her an “oi toy.” Since you can’t elect yourself a skin-you have to be accepted by the family—Jesse’s nothing more than a garden-variety racist at a loss in the big city. “I’ve met some really decent men who were really able to respect a decent white woman. The problem is so many white men are liberal today.” Jesse sits at the kitchen table in a pink T-shirt and silver jewelry, coughing and smoking.

Many skinheads have lived in Jesse’s apartment. The walls of her bedroom are black with graffiti—“Death To The Race Mixers!” “White Power Rules!” “Bound For Glory,” and “people suck.” Each occupant has added his or her own touch, and the room is a kind of shrine to skinheads long gone-Mark Dagger, who’s currently serving time in a Texas prison, and Bob Noxious, who hung a tree stump on the door for dagger-throwing, and has now disappeared to fight the race war in a more hospitable place, perhaps, or to follow the Northwest Imperative: making Oregon, Washington, Montana, and Idaho a whitesonly territory. At the apartment, Dagger’s small son is playing in his bare feet. “What’s the password, Mark?” Jesse asks him, but Mark’s trying to get his head into one of his toys. “Mark! What’s the password?” But Mark’s head is stuck inside his toy. She answers for him: “White Power.”

Jesse’s rap is all about men, about the long line of racist, patriotic, union men she comes from in Kentucky and Missouri. “Growing up, I was around a lot of older men. They’re total racist—for America, for the family. They totally influenced me. Every man in my family did hard labor jobs— construction, welding—the kind of work that made this country great.”

Her image of the past—when America was great—is of great big men and sweaty biceps and drills biting rock and “being out there in the sun working hard to feed your family.” It’s daddy-worship-erotic and childlike; and very wishful. It’s a fantasy about strong men, men who are competent and secure enough to protect their families, about sweet, deep job satisfaction. And then there’s the reality, here’s how Jesse describes her father: “He’s a total racist. He hates it here. He’s here because of the money. He works for the city of Oakland and he’s always coming home saying: ‘Those goddamn niggers can’t pick up their own trash. Filthy mongrels.’’

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

TO PORTLAND

Liz and I leave the city at sunset. The highway to Oregon narrows, climbs, and drops as we pass though mountains, their sides shaggy with snow. The dashboard glows red and from the tape deck come tinny shouts—boot-stomping music, calls to battle. Thor creeps inside the night with His Mighty Hammer-”lightning strikes and thunder roars and cloven hooves storm the shore”—everybody march—“Hail the Order! Hail the Order!”—boot hits pavement, glee jolts the spine—“Life is just a struggle, life is just a struggle, life is just a struggle”—smash—“We are on the Frontlines! Skinhead!”

Cold air creeps into the car. Liz says she could step out right here and disappear if she had to. She could survive in these mountains or dissolve into the safe house network of the white supremacist movement. Once she had to disappear from San Francisco—her apartment was packed up in a half-hour. I ask her why she had to flee but Liz won’t tell me. “There’s eight more years until the statute of limitations runs out,” she murmurs.

When Liz was in art school, she did a performance piece in which she lay naked on the floor in a cold room for eight hours … to see if she could. She’s taken survivalist training. She’s learned how to control her dreams, so that she can save the dream Liz from any disaster.

When we stop at a motel, Liz shows me her survival kit. We’re still on an anthropologist/native basis. She hands me the obit she wrote for two Portland skins who died in a motorcycle accident. It was published in a newsletter for the United White Working Class—a Salt Lake City skinhead group. Brett was 19; Rick, 18 and Liz’s boyfriend. The boys were shooting down a mountain road when Brett lost control of the bike. Liz guesses that he had trouble braking because he’d injured his hand a few days earlier in a fight with a SHARP—a member of Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice, one of the anti-racist skinhead groups. The two boys skidded into an intersection and were hit by a truck. Brett was partially decapitated. Rick flew off the bike and hit the ground; a beer can in his breast pocket shattered and shot into his chest. Liz titled the obit: “Ode To The Death of A Patriot.” One look at the title, and I decide to read it after Liz goes to sleep. She gets into bed wearing her long underwear and Hitler T-shirt—and for some reason I’m moved that she falls asleep so easily in front of me.

As she sleeps, I read: “The death of a brother or sister is always hard to take. We will only lose more before we have our homeland. Even though it only makes us stronger, death in youth is always unbelievable.” She closed the obit with words from an Odinist song by Skrewdriver: “He stood by his people and his people’s needs, and if a man is judged by his deeds, then I’ll see you in Valhalla.” According to Odinist mythology, if you die on the battlefield, you’re taken directly into heaven, or Valhalla; not so if you die at home.

The boys had just visited their mountain hideaway. A lot of the skins have these houses-in-the-woods. They store food and ammunition there. They go there to practice shooting their guns, to play kids’ war games like Capture the Flag. They’ve resurrected the old geography-found virgin land, and claimed it. The Portland skinheads “own” one island in the Willamette River.

“We had our own memorial for them,” Liz says. “When the Vikings bury their dead, they put them in a burial boat and burn them. In a perfect world, we could’ve done that, but we couldn’t set people on fire in the Portland River …” Instead the skins went out to their island and set a swastika on fire. After it burned, they carried it down to the river and pushed it in. At the formal wake (the one given by the boys’ families), Liz took her Honor Cross of the German Mother-a Nazi medal awarded to women who bore more than five children-and, when no one was looking, tucked it in Rick’s pocket. The boys were cremated.

When Liz and I arrive in Portland, we do a tour of downtown, looking for SHARPs. When Liz lived here, the skinheads used to drive around Pioneer Courthouse Square with a Confederate flag waving from the sunroof, blasting white power music-just, it seems, to tick the SHARPs off. Skinhead girls have infiltrated SHARP, found out about parties, or graffiti strikes, then either called the cops or showed up to fight. It’s gang warfare, plain and simple, with 30 to 40 kids showing up on each side. The skinheads are contemptuous of the SHARPs: “I don’t think they actually know what they’re fighting for. They don’t have that fire burning inside of them,” Liz says. “Their purpose is to hate us. They don’t even take an | antiracist stand, just antiskinhead.” But the skinheads also sneer at their squatters’ life—the drugs, the dirt, their makeshift homes. “Skinheads are straight-cut,” I’m told. Liquor’s okay—“it’s European,” and probably Viking. Drugs aren’t—in fact drugs are a black/Asian/South American plot to destroy white culture. The woods and mountains are good-no people, no problem. In their apartments, Nazi memorabilia and white power slogans decorate their walls, and nothing else—no signs of personal taste or history. Hail the order.

We finally spot one SHARP—blue laces, rumpled flight jacket—walking away from the square. Liz takes the corner as he gets to it, hugs it, slows down … makes a face. His startled look is quickly covered by an angry, bruised one. We pass the clinic where the skinheads have joined anti-abortion protesters—“Abortion Is Genocide! White Women Awake!”—much to the consternation of the anti-abortionists. Then we go over the bridge where I can just spot the muddy tail of their island-unreachable in the winter when the water’s high.

Listening to Liz, every encounter with the antiracist skins was a victory. In fact, according to Officer Loren Christensen, of the Portland gang enforcement team, the antiracist skins were, by far, the more violent of the two groups. “They did drive-by shootings and knifings, and tons and tons of assaults,” he says. Their leader, Mark Newman (whom the skins refer to as “the Jew fag”), went to prison a year ago for smacking a girl in the forehead with a hammer-he thought she was a racist skinhead. She wasn’t any kind of skinhead.

After Mulugeta Seraw, an Ethiopian immigrant, was beaten to death in November 1989 by three racist skins, skinhead numbers rose dramatically-from about 75 to 300. Christensen explains the increase: “We’re talking about kids here, and six months after the arrests [of Seraw’s killers] they forgot all about it. Six months is ancient history to them.”

Last summer, one Portland neighborhood declared itself a “racist free” zone. Neighborhood watches were formed to “monitor” skinhead houses. From a local paper: “Those who monitor Heick’s apartment… acknowledge Heick has been careful to keep his nose clean there.” Members of the Coalition for Human Dignity, an antiracist group formed after Seraw’s murder, blamed the rise of skinhead activity on the collapse of the antiracist youth movement. CHD made an effort to pull SHARP back together; pump the kids up.

American Front is generally seen as less violent and better organized than other skinhead groups in the city. The front recruits members by distributing racist literature (many members post flyers in their high schools); by demonstrating-with the anti-abortionists, or against hate crimes legislation, which they consider “Orwellian”; and by making use of any racial disturbances in the area. After a white Portland – man was badly beaten by eight to 12 black guys yelling racial slurs, American Front distributed fliers. Bob Heick claims that the front’s phone line was flooded—many callers asking for more information about the Amenican Front or white racist groups in general. American Front will send members to talk with the callers–but the skins dress down neat and conservative. No flight jackets or iron crosses. They come to your door wrapped discreetly.

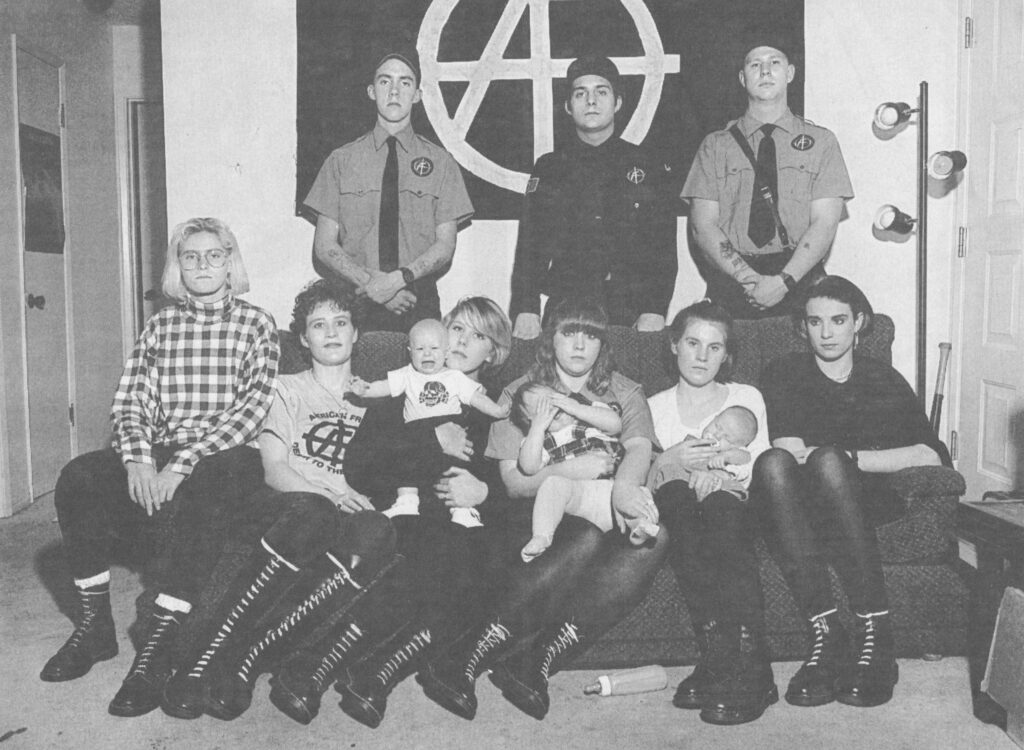

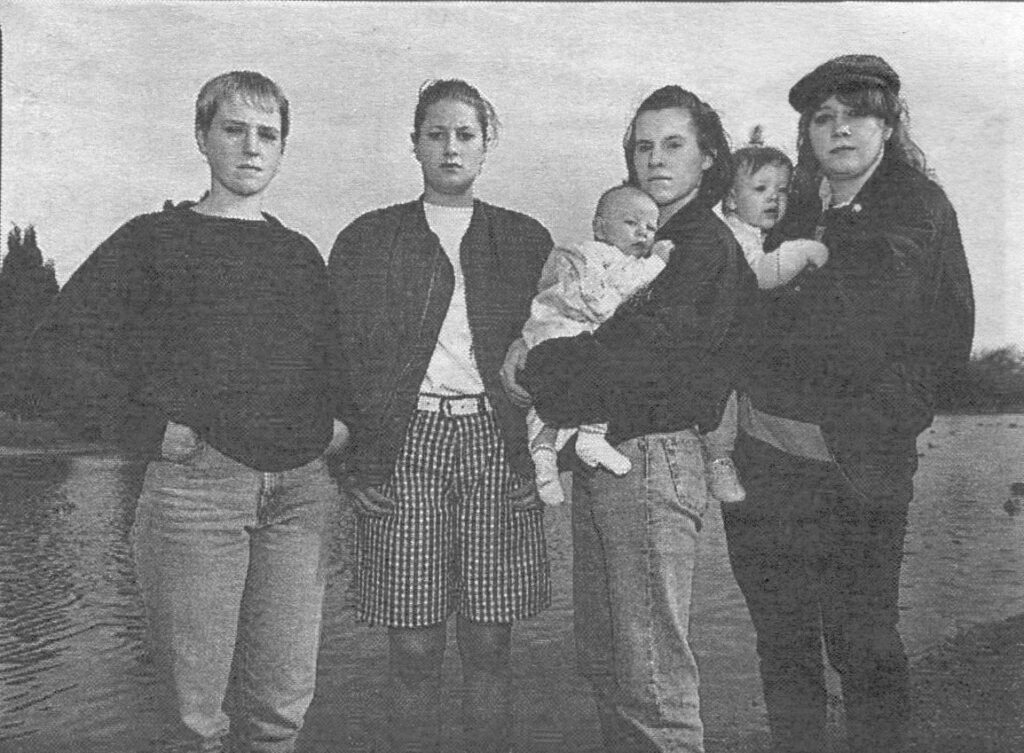

Bob Heick’s wife, Carolyn, has been on the phone, and there are five girls waiting in the living room for us—no bald heads, no uniforms. Short hair, light makeup, pastel sweaters. Carolyn and Kirstin are mothers, now; Laurel’s hugely pregnant. They’ve grown their hair back to protect their children-“It’s a lot easier to protect a child if you can’t be singled out,” Carolyn says. “Babies are more important than your hair.” And these babies are the future of the white race. Hilary and Alice are newcomers, still soaking up the philosophy, trying to win the acceptance of the skinhead girls. They sit self-consciously, watching everything.

When Liz was in Portland she formed the Valkyries, the women’s auxiliary of the American Front. She tried to hold classes in food-canning and first aid (for the coming race war), but the skingirls laughed off her idea. Instead, they wrote and distributed racist literature, planned rallies, and kept in contact with those skinheads in prison. Christensen says: “I can remember four years ago, the women were really subservient. They used to run behind the men like Chinese coolies.” He imagines there came a time when the girls realized that they were the babymakers—he can see them all slapping their foreheads as the thought occcurred—and therefore central to any white race movement.

Carolyn, Kirstin, and Laurel consider themselves “older” skinheads, even though Kirstin and Laurel are only 16, and Carolyn just turned 21. Laurel was the last to grow out her fringe. She’s tiny, with almost pixieish features, but there’s a boldness to her gaze, a hard challenge that removes all impressions of cute. “Sixteen years old is not the time to be grown-up,” she says, her hands folded on top of her pregnant belly. “We just had so much fun. It was such a blast. I never used to worry about getting hurt. Kirstin and I used to go into a fight and never back off.”

Carolyn’s red-haired daughter, named after the Viking goddess Freya, crawls around the floor. After Freya was born, the state sent a social worker to the home—“They thought we’d be goose-stepping on the baby,” Carolyn cackles. Kirstin, milky-skinned and brown-eyed, holds her baby girl in her lap.

Sometimes the girls sound like any group of teenagers talking about other girls”that douchebag,” “that abortion queen.” Talking about the unfaithfulness of guys, but in this case, of white racist guys—“Oh yeah, the guys hate them, they’re ‘halfbreeds’ until they spread their legs.”

The skinhead girls jealously guard their turf-on the watch for “sluts” who just want to sleep with skinhead men, and for rich girls who are just slumming with the skins. “It’s the feline in us,” Laurel laughs. “But I think if the guys were as critical as we are, they’d keep a lot of trash out of the movement,” Kirstin says. That “trash” includes nonpolitical skins, like the guys who join with “the gang mentality,” ready only to party and fight. “They have the politics of Freya,” Carolyn says, nodding at her gurgling kid. “But when you need someone to do the dirty work…” she laughs.

The girls fight girls; mostly SHARP girls. “I think the funnest part for us is that most girls don’t know how to fight. And we had no hair,” Laurel says. Of course, sometimes the guys got mad—“because we beat up their dates.”

The girl they call “the abortion queen” was ostracized after they learned about the abortion (she made the mistake of confiding in Hilary), and heard she was having “race-mixed” parties.

“My first instinct was I’m going to beat her ass,” Carolyn says. “Her ass is mine. I’ll rip her hair out and stuff it into her nose.” But Carolyn, a mother now, decided to stay out of trouble. Instead, she and Bob let the girl’s parents know about the abortion and the parties by leaving a series of messages on their answering machine. “I rocked her world,” Carolyn says. “You mean her parents cared?” I ask, meaning one thing. She answers, meaning something else entirely: “Oh, yeah. At first, they tried to bring the police in on it. They had this assumption we were going to kill the family”—Carolyn laughs at the ridiculousness of that notion. Then the girl’s dad called the house and Bob told him that he didn’t want to alarm the family—“I just thought you’d want to know what your daughter was doing and to let her know, she’s gone—”.

“She’s nothing. She’s completely ousted from any white community. You don’t claim to have racial pride and kill your offspring,” Carolyn says. It occurs to Kirstin that they spend most of their time fighting other white people.

Hilary and Alice both have skinhead boyfriends. Laurel doesn’t quite trust them, especially Hilary, who comes from a wealthy family, lives in the suburbs, and goes to an all-white school. She doubts these two will ever get fringes, will ever become full-fledged skinheads. “I don’t think they can take the spotlight. I think they still want to be able to go downtown in their flats and go shopping. I don’t think they’re ready to go downtown and get jumped by SHARPs.”

But Hilary doesn’t seem to be along for the joyride of it. Her back arched hard against the chair, she listens avidly to everything being said. In fact, her intensity adds a heaviness to the whole proceeding. She jerks loudly into the conversation, earnest and indignant. She seems sincerely offended by the Pink Panthers, who will bash back—“They’re so militant about it!” When the girls begin to make racist jokes, Hilary joins in, but she’s not joking. Their crude caricatures are her dogma.

“I basically got into it by myself,” she tells me. “I was the only one in school who had any racial views whatsoever.” In her white school, the kids are either jocks, trendies, or hippies, she says. And then there’s Hilary. “I didn’t have any friends but I started talking to people outside of school who had the same racial views.”

The other girls come from a more shifting, interracial world than Hilary’s. Each has been in the racial minority, and that experience seems to have been profoundly disturbing. Laurel grew up in a black neighborhood, attended Martin Luther King Jr. grammar school, and went to a mostly black high school. The white kids there were divided into two groups, she says. Some were scared of the black kids and hid in their books; the others “found black life really interesting and decided to go for that … probably just to upset their parents.” She felt sympathy for the first group of kids, and wished they’d come over to her side “instead of just cowering away.”

The day Laurel shaved her head, she seems to have found a rock-hard identity and to have walked straight into the violence she felt shimmered everywhere. “I felt really confident, ready for anything. I felt above everybody. That’s the feeling you have the whole time you have a fringe. It’s kind of a step out-you’re saying that you’re ready to fight for what you believe in. Now there’s no turning back.” She shaved her head in the summertime, shortly after her 14th birthday. Her first day back at school was the hardest, she says. “People let me know exactly how they felt, how they were going to kill me before the year was up.” All they ever did, actually, was taunt her: “Skinhead-Kinhead-Pinhead.”

Though Carolyn was moved all over the country when she was a kid, the few months she spent in California left the strongest impression. She was in the second grade. “In school, there was only me and one white kid. The rest were all Mexicans. It made me feel uncomfortable. I didn’t have any friends. I didn’t want any friends. One thing I noticed, though, was the difference in intelligence between the races.” She then describes a classroom writing assignment from over a decade ago. The Mexican kids raise their hands to ask the teacher how to spell words. “They didn’t know how to spell words like ‘what’ and ‘then’ and ‘going.’ I mean someone asked how to spell ‘silent’—that I can understand.”

Kirstin grew up with her mother and brother in a mostly Mexican neighborhood outside Sacramento, went to a high school that was half white, half Mexican, and got into the punk scene. Her brother had a lot of skinhead friends, but they were older. She met her first skinheads at the mall. She felt comfortable. “What was your first attraction to them?” I ask her. She says: “Because of my school-there were so many Mexicans and the way I felt about it’—with the skinheads, it was cool to talk about it. You didn’t have to keep it to yourself. You could make jokes. Having other people around who felt the same way I did and who didn’t hide it.” That was the only place she could talk openly about race and her discomfort? In the company of white supremacists?

Orwell’s 1984 comes up again when the girls begin to discuss their high school classes. “They’re trying to rewrite everything,” Laurel complains. “Christopher Columbus is not a hero now, he’s a murderer. Now the Egyptians were black. After reading 1984 it scared me. They’re trying to destroy everything they don’t want us to believe. All our old schoolbooks are burned or recycled.”

Kirstin asks if it’s black history month and someone cracks: “Isn’t every month?” Carolyn adds: “You flip on television, and the only cool thing to be is black.” Everyone starts talking at once—“There’s no choice given to whites. If a kid wants to find out about their culture, it’s racist.” And- “Oh yeah, the white Christian male killed every nonwhite.” And—“There’s tribes in Africa who haven’t discovered the wheel yet.” And—“What did blacks invent-peanut butter?”’ Reply—“The cotton gin.” Quick-“No-no-no, a white woman invented that …” Hilary adds plaintively: “I don’t understand how they decided to discredit the people who did it.”

If ethnic identity and ethnic suffering are valued now, what’s a mongrel white kid to do? (Most of the skins are some hodgepodge of Western European ancestry that ceased to mean anything a long time ago.) “What about our history?” they yell. They don’t seem to see themselves as part of the big white backdrop that people of color have charged against for ages, making a mark here and there. They’re just blanks. Because of their white skin, they’ve escaped hyphenation. They’re just American kids; not African-American or Asian-American or Mexican-American. Yet it makes them feel rootless, all alone, without a flag to defend. They want an ethnic community, t00—but what is it? What can it be for a white American kid? They’ve come up with “Aryan” and complain to me: “You can’t find out about Viking history!” Viking?

They want a white history month; they want to be taught white pride; they want everyone in their schoolbooks to be identified by race. The first black inventor, the first white inventor. And here we go tripping, tripping over our own (that is, whites’) sick conception of race.

Kirstin says: “It doesn’t make sense. Black racism is so accepted. People say: ‘Good. They’re proud of their heritage.’ But to be proud to be white is racist. They should be proud to be black. They should stick to their own kind. But making whitey feel bad, bringing up slavery-it’s getting a little old for that. None of us were responsible.” She pauses for a minute: “But they’re not into the guilt as much anymore. They’re coming out now strong and saying the black man is going to overtake us.

“Where do you get that?” I ask.

“In the music videos—they don’t hide it in that. They’re still angry in a way. They’re coming out really violent. There’s the one where they’re killing all the Arizona politicians. And there’s a Terminator X videoit’s really interesting—they say it’s open season on the black man. And Public Enemy telling all black people to arm themselves. It’s the same thing white supremacists are doing.”

Their enemies include everyone but white-minded whites. They have an almost schizophrenic image of blacks. They’ve obviously co-opted certain political constructs—such as seeing abortion and drugs in terms of racial genocide. Liz describes the “tragedy of being a skinhead woman”. this way: “You know how Negro women say: ‘All our men are in jail’? Well, all these white supremacist men are in jail, too.” The skins find qualities they admire in the black community-they say it is tighter, more aggressive about its survival. “If the race war happened now, we’d lose,” Kirstin says. “Blacks are so close together. They’d be real easy to set off and they’d all stick together, but whites wouldn’t.”

But then they say: in the cities blacks are killing each other off, doing our job for us. And they talk gaily, eagerly, of blacks “chucking spears and picking flies out of their hair,” sounding like the most unsophisticated, white-trash racists, like they’re trying to turn back the clock to the time that Jesse talks so wistfully about-once upon a time “when America was great.”

In their mythology, Mexicans are sometimes stupid, can’t speak English, and are taking jobs from whites. Their picture of Jews is not fleshed out at all. The Jew is everywhere and controls the government and the press. The skins want to overthrow ZOG—the Zionist Occupied Government—but the Jew has no face, no attributes, no physical presence.

“Bob gave me a swastika earring—a little, dangly one,” Carolyn tells me blithely. “I used to forget about it and go to workat this sandwich-making place. The boss he’s Chinese—he didn’t care, but the Jewish businessmen would come in yelling: “How could you wear that? Do you know what you’re wearing? Like I was an idiot. I’d just laugh at them. I’m not yelling at them for wearing a Star of David.”

“Do you think there’s any difference between a swastika and a Star of David?” I ask. She skitters a bit: “Well, they get all uppity. It’s just a symbol. It’s been around forever. To completely flip out about it —that’s stupid.”

“Do you know why they’re flipping out?”

“Yeah. Because their parents died there, their grandparents died there, their brother was just a baby and he got thrown against a wall and killed. It’s a joke. Of course people died—why is Jews dying so important? | Why are we supposed to feel guilty about

Jews dying and give them money? Maybe we should feel a little bit bad that people died-but what about other people who died?”

They blow hottest when it comes to liberal whites, politically correct whites, whites who came of age in the ’60s. Many of their parents happen to fit this profile, but so do many media types, teachers, and public figures. Suddenly their language grows biting and imaginative. They talk of “generic whites,” “Caucasian casualties,” and “closet suburbanites.” I’m told that: “Most whites have ‘victim’ printed on their forehead.” Carolyn says: “White liberals go out of their way to blame whites for everything, to prove they’re not racist. Most true racialist blacks hate white liberals more than anyone else. ‘Here, Mr. Negro, take my home.’ They’re big butt-lickers and no one likes a butt-licker.”

Their elders seem to have committed two sins. First, they fucked up the family. Then, they felt so guilty as whites that they traded away their kids’ birthright, their white privilege, for peace of mind. The skinheads talk of the recession, of growing unemployment

and fading hopes—but in racial terms. “When you’re raised to be Ozzie and Harriet but you end up being a white version of Good Times, then there’s bound to be a racial backlash,” says Bob Heick. They talk of the suffering of the white working man and, of course, they’re not alone in this.

Carolyn’s mother was a “hippie”—into the scene for the lifestyle, Carolyn says, not the politics. “The hippies messed everything up, with all the drugs, have sex with anyone in the world,” Carolyn says. Her real father died of a drug overdose when she was two months old—“And that’s why I never got into drugs.” Her mother and stepfather divorced when she was two. By the time Carolyn graduated from high school she and her mom had lived in Illinois (twice), Wisconsin, California (twice), and Michigan.

When Carolyn and Bob got married before having a baby, her mother was “like wow!”—really impressed. “I definitely know what divorce can do and I’m not putting my children through it. Bob and I have said that the only way we’re getting out of this marriage is if one of us dies.” Recently, her mom told her on the phone: “I can’t believe what I’m seeing on TV these days. All these hate crimes. All this white against black, black against white. What ever happened to all that love-your-neighbor we were talking about in the ‘60s?” Carolyn told her: “You loved the drugs back then. You didn’t love your Negro neighbor.”

On my last night in Portland-Martin Luther King Jr. Day-I watch the news with Bob, Carolyn, and Liz; watch the Klan get their asses kicked in Denver by the mostly black crowd of counter-demonstrators. “That took balls,” Bob observes of the Klan. “But it was stupid.” Carolyn and Liz say: “The Negroes are so uppity in Denver,” and turn to me with a gleam in their eyes. It’s the same gleeful triumph I saw in the faces of the white kids in Bensonhurst, holding up a watermelon for the TV cameras, as Al Sharpton and the black protestors marched through their neighborhood after Yusuf Hawkins’s murder. Only there, the kids were almost hysterical with the joy of transgression, and here, in the Heicks’ living room, there’s a cool calculation behind the words. This is their power: to set everyone around them spinning in anger and fear and then sit back and snort—“It’s just a symbol.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

TO IDAHO

At Rick’s grave in Portland, Liz kneels and pins an Aryan Nations button on the small American flag next to his headstone. She starts to read the birthday cards friends have stuck into the dirt, next to a Coors can and a Thanksgiving turkey cutout and a Christmas wreath, and sobs. We drive up the hill to Brett’s plot. Liz kneels heavily and looks at the school photo his parents picked for the memorial. “He hated this one,” she says and starts to cry again. She sticks another Aryan Nations pin on Brett’s flag, and says, “If we forget them, then they’ll have died for nothing.”

After their funeral services, Liz went straight to the Aryan Nations compound. “That’s where the elders are,” she explains. “They could give me more experience and guidance than my friends. And my mom would never understand.” At the compound, one of the men told her: “Yahweh takes his favorites first. He takes his angels.” Liz tells me: “My mother could never understand that because she thinks what I believe in is basically evil.”

And if her mother did understand what Rick meant to her, she’d be upset, Liz says. She’d take it as criticism. For the white power movement is Liz’s family.

She believes that skins are drawn to Christian Identity because of all the violence in their lives. “Our generation of children is lost. We have no direction. Being a skinhead gives you a direction, but there’s so much headbanging, so much death, so many people in jail …” Of Liz’s ex-boyfriends, four are in prison, one is dead. One friend was beaten to death by four other skins in Washington State.

We’re going to see Spring and Annette, the stepdaughters of Gary Yarbrough, a member of the Order currently in prison for armed robbery, counterfeiting, and murder. The Order is a splinter group of Aryan Nations. It provides the Wild West lore for white supremacists, though the skinheads refer to a different mythology: “They were like superheroes.” Order members killed Alan Berg, the Klan-baiting Denver radio talk show host. They also shot one of their own to death—a guy they thought talked too much.

The FBI caught up with Yarbrough and Order leader Bob Mathews in a Portland motel. Yarbrough was arrested. Mathews got away but the feds tracked him down. He died in a shoot-out with them on December 8, 1984. That day is now celebrated as Martyr’s Day among white supremacists. One year, the Portland skinheads rented the same motel room and held their vigil there.

Liz says: “Morris Dees was next on their list for assassination,” referring to the lawyer who broke the banks of the Alabama Klan and, most recently, of Tom Metzger. “That’s great, Liz!” I yell, and Liz’s laugh is startled, uncertain.

As we drive north, we enter mountains and mist, white pines, snow, and mirrored ice. At night, the fog’s so heavy that I strain forward to see something, anything-headlights show only rippling white-push through curtain after curtain after curtain, until I catch myself right at the brink of a panic attack. “It’s a very Viking landscape,” Liz observes.

Spring and Annette live about a mile from the Aryan Nations compound on an unpaved, dead-end street lined with trailers. Chicken-wire fences divide the tiny lots. The sisters’ trailer has faded blue shutters and a small attached porch piled high with wood. Dogs set up their yapping the minute we step out of the car.

Spring, plump and freckle-faced, hugs Liz hard. When Spring turned 16, she got restless and her mother gave her to Liz for a few months—to show her the world. Liz brought her to skinhead communities in Portland, San Francisco, and Salt Lake City. Spring returned to the compound with a fringe.

A Las Vegas skinhead named Mike is staying with the sisters. A former Klansman named Mitch is also visiting. Saturday night, we’re joined by a neighbor-a woman who attends services at the compound’s Christian Identity church. Sunday, Justin Dwyer arrives—a 24-year-old skinhead from Palo Alto, now the Washington State director for Aryan Nations, the political half of the church.

That first night they watch Rescue 911 on the “ZOG-vision.” A black man has been hog-tied by his wife and the cops have arrived on the scene. Both the man and the woman are obviously smashed on something. Mike, Annette, Spring, and Liz are cracking up. They like to watch this show “because you can see the niggers go to jail, and the cops act like idiots.”

After the TV’s turned off, we drink beer and Mike tells me how he became Christian Identity-he took Bible classes led by a Christian Identity skinhead in Las Vegas. Mike liked finding a basis for his racism in the Bible; liked the way the skinhead “laid it all out.” He feels he learned much more in those classes than he ever did in regular schools—“I wish there was more discipline and order.”

A few more beers and the group is deluging me with tales of persecution-how the FBI poisoned Mitch’s dog, and raided the Yarbrough house when Gary was still living there. Gary disappeared out the back door as the feds piled in the front. The girls never saw him again. Spring says that the agents herded them into a bedroom-and wouldn’t let the family dog in with them! The agents teased their dog, took their photo album, ransacked the house … It gets a little hard to take—all the quivering indignation. I interrupt: “You all don’t sound much like Aryan warriors.” The Aryan Nations woman doesn’t get it, but the kids do.

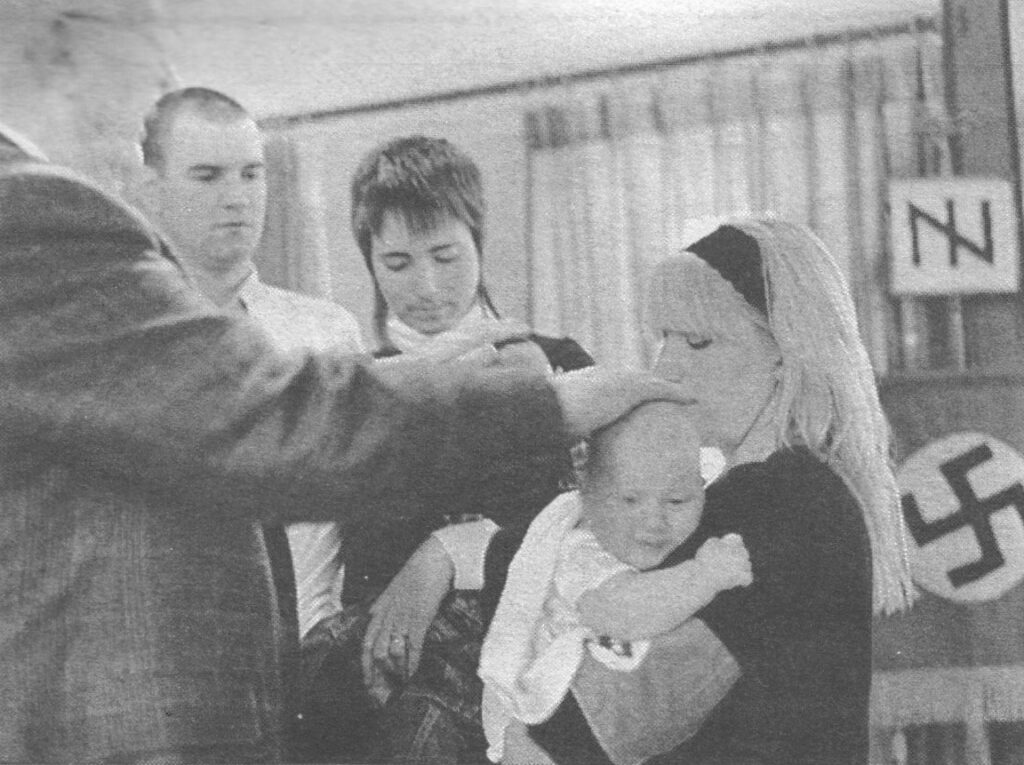

The next day the whole situation is so creepy and depressing that I’m numb. We drive through the white-on-white landscape-snow-filled fields, empty sky—until we see the Aryan Nations flag (a white swastika/cross on a blue shield) at the entrance to the compound. We turn up an icy dirt road, see the wooden signs—“Whites Only” and “Welcome Kinsmen and Kinswomen.” (I’d already been asked my ethnic and religous background-German, French, English, and Christian—so I’m allowed in.) There’s a small wooden church building, rebuilt after it was bombed in 1981, a few cabins and trailers, and a guard tower. Since 1988, Aryan Nations has held an annual Youth Conference here. The skinheads camp out for the weekend and play “traditional Aryan games”—like tug-of-war. “I was Hammertoss Queen three years in a row,” Liz murmurs beside me. German shepherds lope down to meet us, wagging their tails. They only answer to German commands. Of course. The elders-Aryan Nations staff members, all men-come out to greet us.

Inside the church building, there’s a wood stove burning. The flags of the “Twelve Tribes of Israel” are hanging from the walls, only they’re the flags of England, Germany, France, etc. … According to Christian Identity teaching, Aryans are the Chosen People. Christian Identity followers keep kosher and everything—which some of the skinheads find hard to take.

I’m repeatedly told by the men that if I have any questions, just ask. I’m tonguetied. Finally, I sit next to a big guy in a wool shirt and ask him about the animal figures in the stained glass windows. “I don’t know,” he mumbles. I ask him about the flags-he doesn’t know about those either and seems to be blushing, so I get up and walk away. Later I’m told he’s a newcomer and they suspect him of being a fed.

When church services begin I remember the hymns from my Catholic childhood. The head of Aryan Nations, Richard Butler, is away, so the chief of staff, Carl Franklin, gives the sermon. It’s long and pedantic. He dissects the word “woman,” and explains that it means womb of man. Apparently, in the Garden of Eden, man gave his womb to woman to carry for him. There are only about 15 people attending, including four children. We sit on folding chairs. During prayers, people stand and all of the men and Liz give the Nazi salute. Spring would like to salute, too, but her mother “doesn’t think it’s very ladylike.”

Franklin tells me that the skinheads who come to the Youth Congress are looking for the next step. “They’re 19, 20, 21. They want to move on from the skinhead lifestyle. They’re ready to have marriage, children … to grow their hair longer, to keep a job. I think it’s the next phase of the skinhead thing.” Skins have gotten married and had their babies christened at the church. Liz shows me photos from one wedding: the buxom bride wears a white wedding gown, flowered veil, and Doc Martens. The bridesmaids, all blond, are dressed in skirts and dresses—everything a Nazi tan. They’re members of Operation White Nurse, a Las Vegas organization of white supremacist women who learn First Aid and food storage for the coming race war. They aren’t skinheads but date skinhead men. “They’re considered the cheerleaders of the movement,” Liz says. A lot of the skingirls don’t like them—“Too fashion-conscious, too materialistic. At the Congresses, you see them with their blow dryers and crimping irons.”

I ask Franklin how they intend to make this area a whites-only territory, and how they intend to keep it that way. “You’ll find when you have a vibrant white society, this repels the other races because their first inclination is to be unlawful,” he replies. “Take the Negro—he’ll stalk the street at night while the white race is in bed. When you start to enforce civil laws, when you start to get a spirit of freedom and pridethis is anathema to other peoples.” He cites the fact that the Black Lawyers Association moved its annual convention, which was scheduled to be held in Hayden Lake. “They said ‘No way! We’re not gonna go up there. There’s racists there.’ That enforces a white society and it attracts other whites.” And that’s where the skinheads come in“the warriors of the white race,” “the foot soldiers of the movement.” The elders need their violence and their violent reputation. It casts exactly the right shadow.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

ALL THE WAY HOME

“That’s the universal language: violence,” Gordon says. “Doesn’t matter what language you speak, a poke in the nose everybody understands.” That’s what you mean by “Aryan warriors?” I ask. “When people talk about Aryan warriors, they’re talking about final-conflict shit,” Gordon says, referring to the race war. “I believe in it but I don’t think it’s gonna come in my fucking lifetime.”

I ask him about the recent murder of a gay man by skinheads in New York. Were they Aryan warriors? Does that kind of violence serve his cause? “It can get you into a lot of trouble,” he says slowly. “A lot of people look at it as a way to clean up the streets—as a war—as one less fag to take care of. I’m not into instigating anything but… I don’t see. it as wrong. Like that Ethiopian dude who got beat to death, that stuff happens. I don’t know if they went out to kill him or if the beating went too far. I don’t think it’s wise but … Fuck those fucking people—they’re nothing. They fucking breathe my air. They’re just fucking against everything I believe in. But I’m not gonna go out of my way every night to beat someone up, but there are times shit like that happens—you have too much to drink and you go out and put a throttle on somebody.

But how are you guys different from any other street gang? “The difference is that we’re fighting for a cause,” Gordon says. “Not just money, drugs, and turf.” Finally, almost sounding tired, he says: “It’s not all it’s cracked up to be. You’re in a rough environment, you have to be rough.”

Kirstin’s careful when discussing the skinheads’ violence: “I don’t think skinheads will ever get a good rep. There are a lot of bad ones, unfortunately. Like Aryan Nations, we get a lot of trash.”

Kirstin’s still a skinhead but her boyfriend, Kelly, isn’t anymore. He’s grown out his hair and keeps his white power tattoos covered. “He really wants the nuclear family bit. He works hard,” Kirstin says. “He was a skinhead for five years. He’s gonna be 24. Being a skinhead at 24…” Kirstin laughs. “You’re not gonna be that Aryan warrior forever! You sit back like the older people.”

“Little skinheads grow up to be big racists,” Liz says. “Skinhead has a youthful, fun, spunky quality to it. I won’t be doing that when I’m 40. I’ve served my time on the political front. It’s time to retire and live with a group of white power families.”

Somehow, I find it hard to believe in Liz’s retirement—Liz, who jokes that when she takes over the world she’s going to change dictator to dictatress in all the dictionaries. But many of the skinheads seem to long for security.

The skingirls say that skinhead men stay. They won’t desert their pregnant girlfriends or their wives and kids. I doubt the absolute truth of this, but the skins do have an ideology that supports family—and it’s most fervently articulated by the girls. Liz, the unabashed mythmaker, says: “Women are more protected and revered in the movement than in society as a whole. They see us as something sacred, almost mystical.”

Kirstin and her boyfriend plan to marry—a regular church wedding that both their families can come to. (“I don’t want to wear Doc Martens with my wedding dress!” Kirstin snorts.) She won’t be a skinhead much longer either. There’s her daughter to think about now. “No one wants their kids to grow up like that. I want – her aware, but I don’t want her to be a skinhead.” And if their kids befriend, date, or mate with nonwhites? “That’s the nightmare!” they scream.

They want to leave the city, to live on farms in the wilderness, to have lots of children and horses and helpful neighbors. “I’d like to have a whole town where everybody gets along. Like the old days,” Carolyn says. “A place where you don’t have to lock your door. If you need help, everybody will come over and help you build a barn.”. Hilary’s children will walk through the woods safely, they’ll play kick-the-can in the street long after dark—“you know, like it used to be.” For teenagers they’re strikingly, absurdly, nostalgic, but no less so than the twentysomething-year-olds with their television families and ’60s yearnings.

“People need to start getting their working-class values together,” Gordon says. “I feel I would’ve fit in a lot better in the ’20s and ’30s—that’s when America was fucking proud. Now things have just run amok.” The only thing that keeps him going these days, he says, is that he has good friends. “Someday I’ll find a good girl, fucking hook up somewhere—do the white picket fence thing.”

Funny thing about Gordon-he rejected his parents’ middle-class lifestyle and their expectations of him; refused the smoother road they paved. “It was—go to high school, be on the football team, do all the fucking things kids are supposed to do, then go to college, be a doctor, have a couple of kids when you’re 30.” But Gordon says that ever since he was a kid, all he wanted was his own family. He got married at 16 and had three children. “I was working three jobs, busting my ass but my kids always ate …” He describes this period of his life as an achievement: “I slept in the bed I made. I took care of business.” After four years, his wife “fucking twigged out” and ended the marriage.

I ask Gordon: “Do you think it matters to anybody-you working hard, raising kids, taking care of a family?”

“Oh, yeah,” he quickly reassures me. “That’s the idea behind this whole fucking thing.”

They’re trying to repair what they think were the damages of the ’60s; finding family and community in the color of their skin. They’ve pumped themselves up with the politics of supremacy and given to ordinary life—babies, marriage, job—a “heroic” mythology. They say: We’re propagating and preserving the white race; we’re recovering lost white working-class values. It’s the white white picket fence thing.

After I returned to New York, Laurel had her baby and Kirstin went back to high school. Kiwi was arrested for assaulting a cop in a bar (he didn’t know the guy was a cop), but the charges were dropped. Liz decided it was time to leave San Francisco. She went to Spokane, Washington, where she moved in with Justin, the Palo Alto skinhead—not a bit of street to him and a bright future at Aryan Nations. The night Liz left, Gordon and Kiwi were arrested. Both are charged with attempted murder.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~