Stick Men and Giants

Inside the Rikers Island AIDS Ward

By Kathy Dobie, photographs by James Hamilton

First appeared in The Village Voice, Dec. 4, 1990

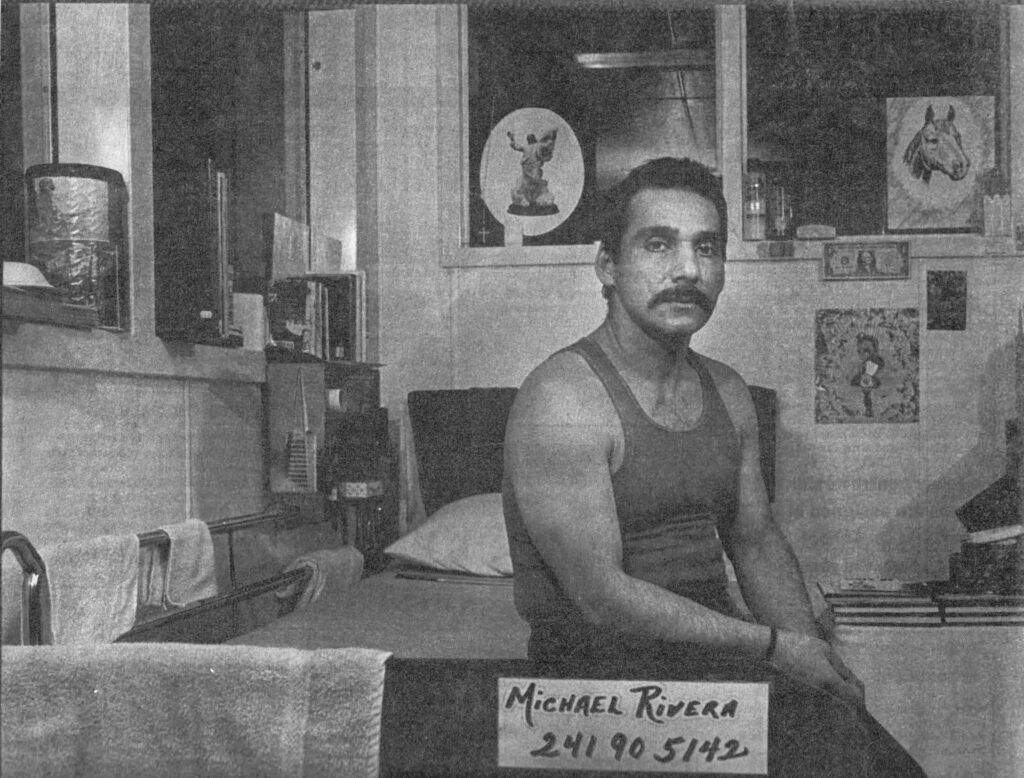

Guillermo just lies there. Collects his phlegm in little paper cups. He hardly gets out of bed and when he does, he often gets back in with his shoes on. He’s turning into a stick man and spooking all the guys in the Rikers Island AIDS ward. Michael Rivera tries psychology: “Look at you-sleeping on that filthy bed. Get up and change the damn sheets. You’re just using the disease. You look like a little baby. There’s no one in here who’s gonna treat you like a little baby. That’s what you want? Oh, here, koochee-koo.” Guillermo gets up in a rage, changes his sheets in a rage, stalks to the dayroom and eats in a rage. “You know you did all this ’cause you were mad,” Michael tells him that evening. “You’re right,” says the sick man. “I wanted to tear your head off.”

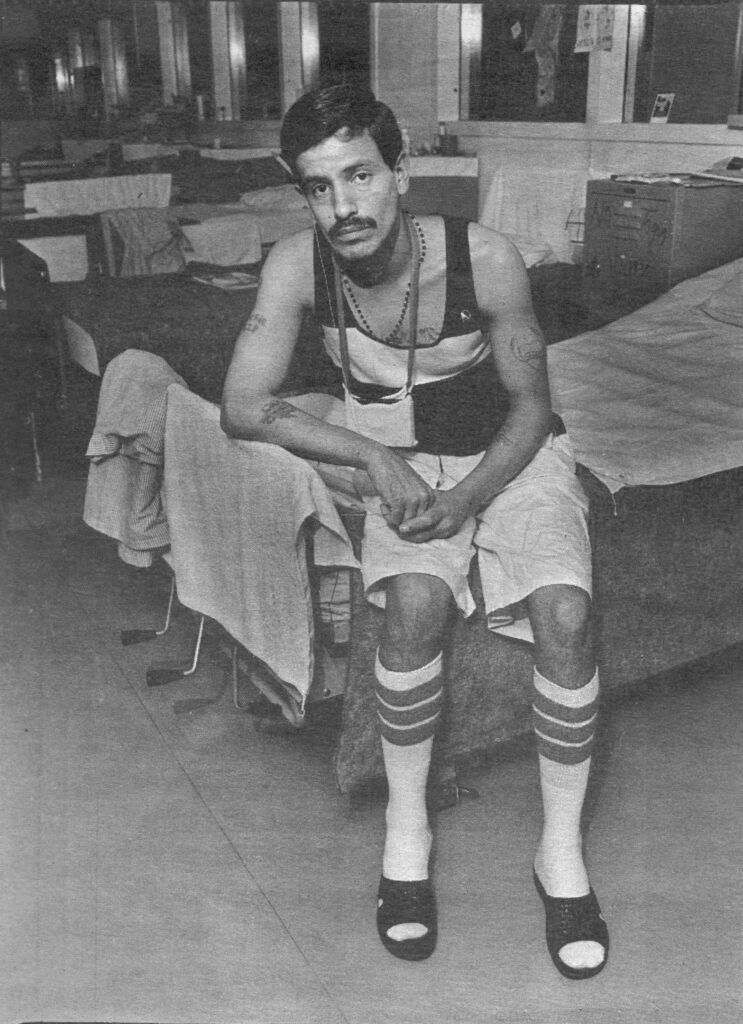

“The shit that I got,” “the Monster,” “the Luggage,” “the Big A.” Last April, I met a group of men at the Rikers Island AIDS ward. Over the next four months I interviewed them. Michael and Ignacio remained at Rikers, which is supposed to be a short-term holding facility, during that time. Michael, arrested for selling cocaine, was waiting for his case to be decided in court. Ignacio, already sentenced to do state time, was held there because he was taking ddl (experimental drugs are generally not available in the state system). Padre, Oscar, and “Steve” (who doesn’t want even his first name in print) were sentenced and shipped to prisons upstate, disappearing as best they could into general population. Their crimes were money-seeking ones related to their addiction-burglary, selling drugs and their sentences are short, but they don’t know if they’ll outlive them.

In the New York state prison system, the life expectancy of a person with AIDS is less than half that of people outside. According to the most recent study, as of 1987, prisoners with AIDS lived an average of only 128 days following diagnosis, and that figure had been declining; almost a third of the inmates who died from AIDS were not diagnosed until autopsy. As of October 1990, 920 state prisoners had died. Each thinking he or she was alone. Hidden in general population, the prisoner with AIDS lives scared that the other inmates will discover he’s sick, that he will become skinny and weak and unable to defend himself, and he lives locked up far away from his family and community. Education of staff and prisoners about the disease is minimal, so fear and prejudice are high.

In Sing Sing, an inmate with Kaposi’s sarcoma dashes in and out of the showers, trying to hide the sores on his legs. He had passed the virus on to his wife, she died, and his six-year-old daughter is in foster care. He walks like an old man, another inmate reports, tormented by guilt. The men begin to ostracize him, and then in a sudden turn of compassion, decide to help him die. They start collecting money so he can buy enough dope to kill himself, then the prison officials take him out of general population and bring him to the Sing Sing infirmary.

Prison infirmaries are not equipped to treat the many AIDS-related diseases, and many local hospitals refuse to treat AIDS inmates. When Oscar arrived at Franklin Prison, he says, the infirmary doctor discontinued his pentamadine treatments for two months, while the infirmary ran its own tests to confirm his diagnosis. Oscar lost 30 pounds and his T-cell count dropped to five (the normal range is 1000 to 1500). They treated him for asthma. He had PCP. (Franklin has not replied to Voice inquiries.)

Many men spend the last months of their lives in these prison infirmaries surrounded by nurses and physicians who are leery of them, without access to programs or counseling-just four walls and their own thoughts. Unlike the city, the state has no Compassionate Release program. Oscar’s friend died after four months in the infirmary. At the end he was living on faith alone, Oscar reports. Hoping he would get out of prison and down to Puerto Rico to see his mother. It didn’t work out that way. He died in a jail on the Canadian border.

But back here at Rikers, there’s another kind of incarceration for prisoners with AIDS-Dorm 4. It’s a ghetto—and that cuts both ways. It means that every officer who takes the men to the yard or court knows they have the disease. “Dorm 4,” just code words for AIDS. The men are often segregated in the court bullpens, there are court delays because lawyers, judges, and officers don’t want to handle AIDS inmates, and the men aren’t returned to general population at Rikers because they are marked, and fear being ostracized, beaten, or slashed (which is why most prisoners in this article are identified only by first names). A former inmate recalls his stay in the general hospital ward-twice the men tried to suffocate him in his sleep. The lights were bright, lit from 6 a.m. until 11 p.m., as regulations require. The inmate suffered from terrific headaches and one day he just lost it and tore the lights out of the ceiling.

In Dorm 4, the lights are kept low, and the sicker men doze all day in an artificial dusk. Montefiore Hospital provides 24hour medical care, there’s mental-health counseling, and access to the city hospitals. Weekly community meetings are held in the dorm, and because the inmates demanded it, a Montefiore staff member must attend to answer their questions. Many men learn enough about AIDS in Dorm 4 to save their lives when they go to the prisons upstate.

Everyone’s got It here—”You see the death around you, and that stress is a killer,” says Michael. But the inmates counsel each other. “A lot of people come in from the outside and they’ll talk about AIDS and about the feelings,” Michael says. “But how can you really understand it if you don’t have it? You’ve got to really have that fear in you, that hurt in you, that you’re saying to yourself, ‘Wow, I’m gonna die.’”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Dorm 4 is the third incarnation of the Rikers Island AIDS dorm. At first, inmates with AIDS were kept on what should be the infamous Third Floor of the Rikers Island Hospital. Kept in single cells with paper sheets on the beds in a rat and roach infested building. No medical care, inadequate diet, no rec programs or counseling—a lot of men died, and died painfully. The men of the Third Floor rebelled-hunger and medicine strikes brought in the press and then U.S. District Judge Morris Lasker. The threat of a federal court order built Dorm 18 in 15 days. Montefiore took over the medical care from Prison Health Services. Dorm 4, with 26 more beds and isolation and semi-isolation units, was built in May of 1989. Dr. Charles Braslow, program director at Montefiore, says, “I’m proud of what we do there [in Dorm 4] but it’s less my doing than those inmates on the Third Floor. If they hadn’t kicked up a ruckus, they’d probably still be there.”

Dorm 4 is now widely considered a model of humane and efficient care. Corrections proudly brings visitors through. Official history and the bureaucrats will erase the men of the Third Floor, but bits and pieces of what they did are still passed on to the current inmates in the stories of Officer Sylvester Brown, who has been with the men from the beginning, Ignacio, who was incarcerated in Dorm 18, and Steve, one of only two men left alive from the Third Floor. Steve says: “See, most of the people that were on that Third Floor, they’ve been wrong all their fucking lives, including me. But all of a sudden, the right hand became the left and the left became the right. All of a sudden, we weren’t wrong anymore. They were wrong.”

“Dorm 4? Isn’t that the AIDS dorm?” says one officer to another, giving Michael Rivera a funny look. “Yeah but you don’t have to worry about it,” says the other officer. “They’re kept all the way in the back and they’re secluded all by themselves.”

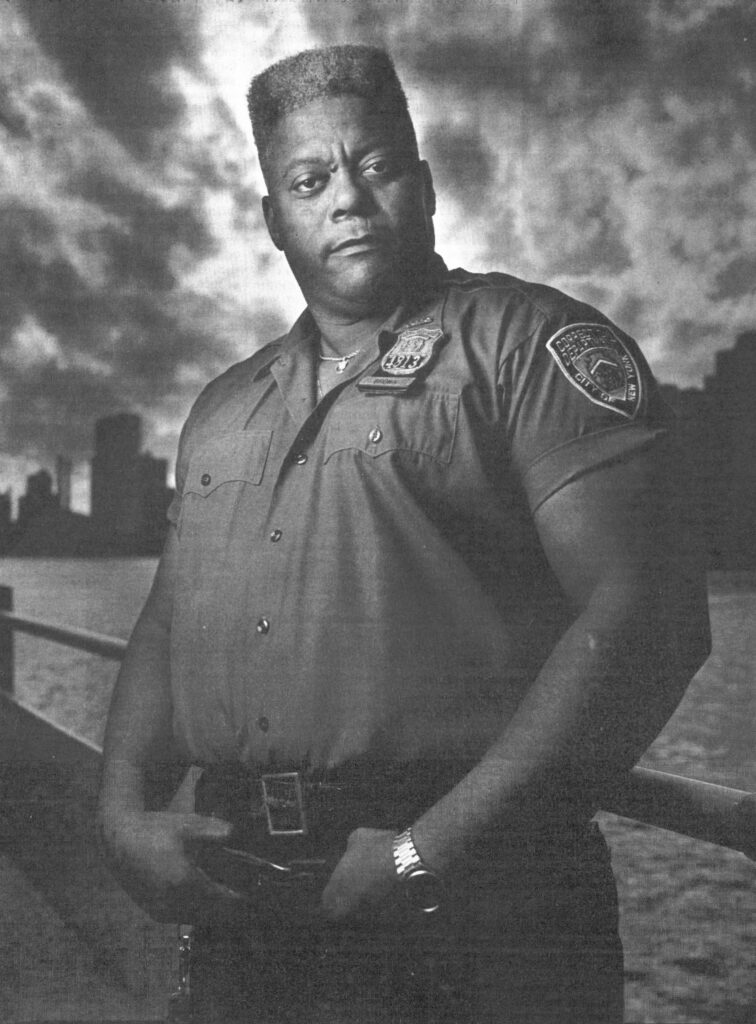

Many gates slide open, the long hallway twists one, two, three times but then you’re there. Officer Brown is standing in the Bubble, a glassed-in command station with a view of Ward A, Ward B, and the dayroom, where a group of inmates is watching The Abyss on the VCR. A tree trunk of a man with a shock of silver hair, and a voice that booms—“All he wanted was a cigarette! A goddamn cigarette!”—Brown laughs and stamps his big foot down and pencils and paper jump up and fly around. Switches track midsentence, rushes on, shaking his head, throwing out his arms and telling someone he’s “a gentleman and a friend.” Then he’s giving out ice cream to a line of inmates, the men he calls his children. “All of a sudden this place is becoming an air traffic joint,” he says, as we all crowd into the Bubble, as an inmate comes to the window, as a c.o. comes in for keys, as the interview continues.

“What you see here is the third generation of AIDS inmates,” Brown says. The inmates call him Mister Brown, because he calls them Mister Rivera and Mister Williams, not inmate this or patient that. Brown volunteered for duty on the Third Floor. “That first generation-boy, they caught hell,” he says.

He’s worked in the Bing—the maximum security unit-played the hardass officer role to the hardass inmate role. He’d rather be here. “This is probably the only type of inmate you’ll see that black, white, and Hispanic get along together-especially blacks and Hispanics who are known to fight one another! I mean, it’s the arch rivalry in the big jails!” Big jails gave him his gray hair, broken knuckles, and high blood pressure.

He tells me the inmates had a “big powwow” here last night. Cooking food until 11 o’clock. “Blacks and Hispanics, you know, they all eating, eating out of the same bowl. Usually they don’t allow this in a regular jail.” Another officer panicked—“What are you gonna do with that?” he asked Brown. Like the salami and rice were rioting. “I said, ‘Let ’em cook, man, let ’em cook. It’s promoting unity.’ And that’s the way I do it.” Brown says the guys don’t fight each other because they know they’re huddled against the world here. Prisoners with AIDS-it’s “us” and “them,” and them don’t care much.

Tells me about a guy who came in with an attitude and a wheelchair-couldn’t do nothing for himself, wheeling into things, bumping tables, chairs, knocking them over, a wreck of self-pity. In two days, Brown reports, he was out of the wheelchair, walking.

“What do you think changed?”

“The guys, the guys. A new guy will come in here and look around and say, ‘Look at this guy-he’s got AIDS and he’s walking around, he goes to gym, he’s lifting weights, he’s pushing up. Hell-I ain’t gonna have them call me no chump. I ain’t no chump. I’m getting out of the wheelchair.’ ” Many of Brown’s stories end right there-at the moment the guy gets out of his wheelchair and walks, or the guy throws off his depression and pitches in. A new inmate arrives at Dorm 4, screwed tight, eyes blazing, uhoh!, and all he wanted was a “goddamn pack of cigarettes.”

Brown was a marine in Vietnam. He calls Ignacio, an older inmate, his senior man.” When there’s trouble with the inmates, arguments, apathy, the bitterness-that-willnot-get-out-of-bed, Brown talks to Ignacio who talks to the guys. Ignacio’s been in the ward for two years, longer than any other inmate-“I respect a senior man, says Brown. “He keeps it alive.” Ignacio came to Dorm 4 from Dorm 18, where he met a lot of the men who came over from the Third Floor. Heard the stories, felt the solidarity. “Whenever I have any little problem, Brown says. “I get him to talk to his troops.”

And when the troops aren’t listening to Ignacio—too new to the dorm, too angry, coming from lives too disorganized to respect a senior man-Brown brings out his magic tape, a TV documentary on Dorm 18. It shows Ignacio helping another inmate who’s hooked to an IV get into his shirt, and Officer Brown doing push-ups with inmate Steve. Officer Ernesto Blanco talks about how other officers back off when they find out he works with AIDS inmates. It’s only a few minutes long. It’s enough. Steven and Ignacio gain stature and authority in the eyes of the other inmates, and a picture of community in isolation is sketched.

“I put the tape in. I go in and watch it with them. Shoot! A couple of hours later, the table tops are clean and ‘Mr. Brown, Mr. Brown, you got the soap powder?’ Guys in wheelchairs trying to work! It cuts through that whole unrest thing.”

Watching it one afternoon in the dayroom with Michael: The anchorman describes the Rikers AIDS unit as an “unusually gentle place.” Michael laughs, short and soft, and repeats the word “gentle.” Then Steve is on the screen, survivor of the Third Floor, talking about how once officers shoved food at him with a stick, and how far the system has progressed. Then a shot of Steve lying on his bed, looking off, away from the camera. Signifying thought. In living rooms all over “America, people watched the prisoner with AIDS looking off into the distance. What does he see? Disease? Prison bars? Early death? It’s all very vague. It’s so sad (in that vague way), it’s pretty. Then Michael leans over, whispers, “Look at the anger on Steve’s face.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When the last gate slides open, you’re facing Ward A. Like a nursery, a fishbowl, a 200-glass windows on two sides of the room where you can stand and watch 20 men inside lying turning moving on their beds. Many visitors come through here to peek at their symptoms, to measure the progress of dementia, to ask: How does it-, how does it feel, how does it feel to, uh… have It? I am one of them.

Michael says it hurts to talk. “As I’m saying the words, I can feel them, and you probably hear a little tremble in my voice. And I am, I’m being hurt, but I like to get it out.” He has large hazel eyes, a head that seems a shade too big for his body, dark hair, dark and silver mustache, handsome.

The men didn’t like the new dorm at first-the women’s toilets, the invalid baths, the baby beds. Bathtubs with seats? No urinals in a men’s jail? They were insulted. It was designed for invalids and the men don’t see themselves that way—“We are fighting for our lives,” Michael says. Once he was coming in from the yard and an officer announced, “Yeah, these guys all got AIDS.” Said it to another officer with a group of civilians around. Michael waited until the handcuffs were off. Then he caught up with the officer, told him he had broken the confidentiality law. Michael was angry. People gathered around. A captain was called, the officer made to apologize. “I don’t want him to lose his job but I think you should educate your officers,” Michael told the captain and the captain agreed. When Michael got back to Dorm 4, the guys had already heard about it. “All right, Michael!” “Chalk up one for us!” For us.

“Sometimes anger helps with this disease,” Michael says. “When I’m angry at the system, it gives me a little more strength inside. I refuse to let myself deteriorate in here. I refuse to let myself die in jail.”

He speaks most often of “the guys in here.” The guys in here, every single one of them, are afraid of dying in jail, of dying alone. They’re afraid of losing control of their bowels, of losing their minds—they see it happening to each other. Some of the guys in here are afraid that they’re guinea pigs for new drugs, new treatments. Some of them are afraid of a breeze coming in a window-pneumonia!

Michael’s an artist, and the father confessor of Dorm 4. Men come to him when their marriages end, when they find out their babies have tested HIV positive. When Oscar’s father had a stroke, Oscar closed the door of the tiny law library, sat inside with Michael and wept. They ask him for legal help, doctors ask him to explain medical procedures to other inmates.

A charcoal drawing of Nurse Lighty holding a cat hangs on one wall of Ward A. Across from her, above Guillermo’s furrowed bed, hangs a half-finished pastel of the Virgin Mary. The inmates bring Michael photographs of their wives and girlfriends and he draws their portraits in charcoal and pencil.

When he was a boy, Michael got into the High School of Art and Design and went excitedly home with the news. “Hey, Mom!” But his father said no son of his was going to be an artist. No, his son would do a manly job—“and a man’s job was plumbing.” So Michael went to Morris High, quit, got married, and worked as a plumber with his father. “Sometimes I think if I could’ve gone to the school I wanted, maybe my life would’ve turned out differently.”

In ’88, he was diagnosed with chronic salmonella and PCP. He was sick for a while before he went to the hospital, but he figured it was walking pneumonia until he passed out. “You have AIDS. You’re dying,” he remembers the doctor saying. A hospital social worker came by and picked up the pieces. Talked to Michael a long time.

In the hospital, he told two of his five brothers. The three men cried. Tom shook his hand and then grabbed Michael and hugged him. Michael put his hand out to Hector—“And he pulled back. You could see the fear.” Michael was gonna let it go, but Hector shook his hand and then hugged him. “As time went on I sent them articles and books and had them talk to my doctor.” He’s not telling his parents. It’ll hurt them too much. They’re old, Michael’s 41, and he thinks he’ll outlive them.

At night, the Artist is on suicide watch. Michael’s a suicide prevention aide—one of only two jobs available to the inmates in Dorm 4. “The only light that’s on is in the bathroom. A lot of times I’ll take a book and I’ll take my chair, put it in the bathroom and I’ll read all night long. I’m all by myself, nobody bothering me, nobody asking me questions, nobody asking me for any kind of help, and that’s nice. I go for that.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sometimes the DOC representative can only bring me to Rikers in the morning. Nine a.m. and Michael’s still in pajamas. His bed’s at the entrance to Ward A. The ward’s mostly Hispanic. Most of the men contracted the virus from needles. There are only a few gay men in the ward right now—some of them got it from needles too.

Nobody sleeps well at night and mornings are insulting-get up … for what? go… where? Guillermo’s always in a blue bathrobe and always in his bed. Michael says he’s begun to talk in his sleep. Talks a lot of nonsense and when he sees Michael, he sings “Mi-kie, Mi-kie” like a baby. He’s so wasted now, the inmates have gone to the doctors and asked them to send Guillermo to the hospital. “He’s not eating, he needs someone to feed him.” In the bones of Guillermo’s face, Michael has seen Death, and the men don’t want It lying right next to them, in a bed like theirs, babbling all night in Guillermo’s voice.

Behind Michael, on the other side of the window, something slices the air, a head appears, disappears—wap! wap!-fury. What the hell? “That’s Shorty, killing flies,” Michael laughs. “He’s got a war on flies for some reason.” Shorty shoots in and back out of the dorm, brown eyes dancing, fixing me with a grin on the way. When I first spotted him, I thought, how cute! how impish! How wrong. If Shorty were a drug, he’d be an amphetamine. Michael laughs, “We call him Speedy Gonzalez sometimes.” He’s short and short-tempered so Shorty’s not a bad nickname either.

Shorty’s been locked up for two years now, survived back-to-back pneumonias, and he’s waiting for a judge to decide if he can go home through Compassionate Release. The doctors at Montefiore can recommend that an inmate be released, but the final decision rests with a judge. The process can take a long time, too long for some. According to Susan Hendricks of the Legal Aid Society Special Litigation Unit, delays can be caused by an inmate becoming too ill to appear in court, by a lawyer who avoids a client with AIDS, by a judge who’s reluctant to release an inmate who’s not bedridden.

Medical testimony is hard to get. “The doctors at Montefiore are not willing to come to court and testify,” says Hendricks.

A spokesman for Montefiore says that its physicians are already overworked and can’t take time away from patients to spend time in court. Legal Aid will hire outside doctors to go to Rikers and examine an inmate, but it costs too much, Hendricks says, and only a handful of doctors are willing to take the time from their practice.

Some judges and lawyers feel an inmate is better off in Dorm 4 than on the streets, she says. “And it may be more malevolent than that. It may be that everyone’s just waiting for the client to die.” Often, healthy-looking inmates are told by judges to come back when they’re sicker. That, to a man with a T-cell count of 12. The men at Dorm 4 sometimes prepare for their court appearances by wearing baggy clothes and trying to look as disheveled as possible.

Shorty had his day in court but the judge wanted documentation of Shorty’s recent rashes. Michael calls Shorty’s lawyer, the lawyer’s not there. He leaves a message: We have the medical records, when’s the court date? The lawyer can’t call Rikers, they hope for something in the mail soon. Shorty doesn’t speak any English, his lawyer speaks no Spanish. “So it’s kind of hard to figure out their relationship,” Michael says.

Steve once described Shorty as “an ornery son of a bitch” and Shorty probably feels the same way about Steve. They fought once in Dorm 4. “Can you imagine that big giant guy against this little guy here?” Michael asks. He tells me the story of the fight: “Pussy” spoken like a kiss; a flying object; a little blood on the face; “that little motherfucker cut me,” said in wonder; a punch; a flying person, flying backwards and hitting the wall; then the uneven free-for-all. Steve ended up in isolation and Michael visited him there, bringing him books, coffee, and cigarettes. “Yeah,” Michael laughs, “he did a good time in there.” He would’ve done the same for Shorty. Both men are his friends.

Michael remembers when the inmates heard that Steve had been arrested again they knew it was only a matter of time until he was brought into Dorm 4. “I was looking forward to meeting him,” Michael says. “I had heard so much about him that he was a fighter. I said, “Maybe I could utilize him.’ I felt like I was all alone.” When Steve got there, everyone was shocked. “He looked really bad. He was so skinny. Even I said, ‘Oh my God!’”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

After a month, Steve began to put on some weight. Then he started working out. Steve has survived four bouts of PCP and recovered from a case of cryptosporidiosis diarrhea that his medical records describe as untreatable. His multiple resurrections, his ready and visible anger, his years spent inside state prisons, his place in the rebellion on the Third Floor give Steve authority in Dorm 4. Steve tells the men here: Watch out when you go upstate-nobody gives a fuck about you there. As impressed as they are by Steve’s transformations—stick man, giant, stick man, giant—they seem even more impressed by Anthony Mercado, who was big one day and dead the next.

A lot of guys arrive at the dorm in shock. They’ve just been told they have AIDS, and they’re still in denial. Padre came to Dorm 4 straight from Kings County Hospital, where he was diagnosed with PCP and AIDS. All around him guys were dying. “I seen a lot of guys going out. Kicking the bucket. It fucked me up. I know that. You talking to them one minute, the next minute they’re bagging them up, taking them out. Goddamn.” He was shut up tightWhy me, God? He’d stopped shooting dope for a couple of years. He was smoking crack, yeah, but he felt like he was on the verge of straightening his life out. Felt that way because all his life Padre wanted to, and all his life he couldn’t. He has lived for over 20 years with that desire, that voice in his head: I’m gonna do it. I gotta do it. Take hold of things, start again, do it right. Then Padre had AIDS and it was like God said: Your desire never meant shit.

There, in Kings County, Padre said to himself, Goddamn, I’m gonna die. “I didn’t want to kick it with nobody. I just kept stuffing it down like there was a sponge in my stomach.” Then Padre was in Dorm 4, and I met him. He wanted me to know that he was a man, straight up. Slapping his chest—This is a man you’re talking to! He liked girls, okay? In fact, he might’ve gotten the virus from girls. Yeah, he used to shoot up, but with his own set. Well, sometimes he shared.

“Once they admit to themselves they have AIDS, they’re hungry for any information they can get,” Aush Byla says. Formerly a keyboardist for Steppin’ Razor, an all female reggae-funk band, Aush now teaches writing and GED classes at Dorm 4. “They’ll want to have a class on AIDS where does it come from? What can I do about it? After they get the information, they either become totally depressed, lie down in bed and don’t get up; or they get like Oscar with his letter-writing campaign.”

It was the sight of John Cardona tottering back into Dorm 4 from Bellevue hospital barefoot that launched Oscar’s campaign. Aquino caught Cardona, helped him to his bed. He wrote his first letter in stuttering disbelief. Then Cardona died. “I’ve personally known of four men who died here at Rikers Island of AIDS and still know many more who are on their way to meet death in jail,” Oscar wrote. “Most, if not all, who are suffering from this disease cannot bail themselves out of jail because bail is set at a price that is unaffordable. We are not wealthy individuals and our families are poor and struggling themselves. Where is the justice? Where is the compassion?”.

Oscar closes the letter: “This I write with the support of the Men of Dorm 4 for all the men after we are gone who will have the glory to go home and die with dignity and honor, with their loved ones, with their families.” Thirty-five inmates signed the letter. Oscar sent it to Senator Moynihan, Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, and the State Commission of Correction. He got form letters back from each of the offices. Oscar was impressed-hey, this works!

Other men started writing letters, writing the stories of their arrests—saying their medication is thrown away, and that they wait in cells for days without methadone, without AZT; stories of bullying cops, of being segregated in bullpens. The guys who couldn’t write or were afraid of the blank page were interviewed by other inmates. The inmates’ stories, those that are personal, not political, that are not critical of the cops, of the justice system, or of the jails, are being published by John Jay College, on contract to DOC. Aush says she edited out the critical stories, believing DOC would balk. A story about an officer who started a riot in a bullpen by announcing that one of the prisoners had AIDS will not be published. A poem about being alive, titled “Privileged Guests,” will.

When Aush was trying to get the critical stories published, one inmate asked her why she was putting her job on the line for them. “Why? We’re just a piece of shit,” said the inmate. “That really threw me,” Aush says. “I had to think about that one.”

She’s worked in Dorm 4 for a year and a half now. It’s taken her that long, she says, to get to where she can talk to the inmates about anything, “like the herpes that’s in their ass and crawling up through their body.” The guys told Aush that when she first arrived, she looked scared. What she remembers was shaking an awful lot of hands. It was weird-they’d be shaking her hand, ultrapolite, and telling her some creepy story at the same time. “At first, they all presented themselves as career criminals—as Charlie Mansons.” Officers, staff, even reporters get put to the test. They’ll ask a new c.o. to borrow a pen. Michael says he’s watched officers wipe off the returned pen with an alcohol pad. But a lot of times it’s just that moment before the pen or hand is offered, a beat of hesitancy, the eyes widening, then going blank, that gives the newcomer away.

“Sometimes I’m the first one to hear their three-year-old has been diagnosed as HIV positive,” Aush says. “They’ve been tested so much, they either go along with being psychopathic deviants or they try to fool the psychiatrist. So they’re not gonna go to a shrink with their problems. They’ll go to Officer Brown, they’ll come to me. Christie’s grandchild just died. He came to me. He said he didn’t want to grieve in front of the guys. Then the guys saw him dry-eyed and said, ‘Oh, he doesn’t give a shit.’” Aush laughs: “I said to him, ‘Could you cry a little? ”

Aush started a psychology class. “I had a group of guys that considered themselves the elite. They had their GEDs, they’d come in with their psychology books under their arms, we’d close the door. They really took pride in the fact that they were attending this seminar.” They talked a lot about stress. “They had no idea it does a number on your immune system,” Aush says.

Hot Cuffs recently died. Aush says, “I guess he had a lot of time to do and when they have a lot of time to do, they don’t fight.” Hot Cuffs got his name from a story he wrote for Aush’s class about his arrest on Labor Day, 1989:

“Errr… He has AIDS,” the desk sergeant roars.

“Yeah. I caught it from your mother,” I angrily quip back.

“Cuff him!” the desk sergeant barks to the cop. I think I’ve said the wrong thing.

The cop puts one cuff on me. Then a cop… pulls out his lighter and heats up the other cuff with it. I can see it coming. The hot cuff is slammed on my other wrist. The nightsticks are pulled out. I’m being beaten on the head and legs!

The story ends when Hot Cuffs—Peter Augustine—gets to Dorm 4 and the “doctor on staff has to drain the burn on my wrist from the hot cuffs. My wrist is infected.” Hot Cuffs is dead but I like to think of the desk sergeant and the arresting officer reading this, and twitching a little. Of Hot Cuffs tunneling into their dreams, a long hand, those scars gleaming; plucking them, sweating, from their sleep. Wha-a-at?!

A picture of Jesus, robes flowing, clouds foaming at his feet, hangs above Michael’s bed, and moving toward us, between the rows of beds, comes a man whose body ripples like water. Pete the Barber he’s called because he cut hair in Green Haven prison. Pete applied for Compassionate Release and had his day in court last week. The judge wants two weeks to peruse the medical documents and Pete’s record, to make an informed decision, or to avoid a decision altogether.

The Dorm 4 doctors have suggested to Pete that he go to Goldwater Hospital. The men here call Goldwater “the death house.” DOC has six chronic care beds there for the terminally ill. When there is no treatment left, no reason to go to the hospital anymore, when you’re not going to recover one more time, no more miracles of science and will, when you have turned to bones and water, then they send you to Goldwater. Pete doesn’t want to go. Pete wants to go home to his wife and three teenage sons in Staten Island.

“How’s the article going?” Pete asks. Last week, Pete, Al, and Michael discussed the article with Aush – deciding who else I needed to talk to. Aush asked the three men how they thought I should handle the subject of their lives outside: the common slide back into drugs, the disintegration. When we first met, Aush had said to me that she gets the best part of these men’s days-gets them when they’re cleaned up literally, and cleaned up from drugs. I carry a horrible picture in my head, one I’m not comfortable with, of Death pulling the men from chaos and as it pulls them, they become clearer and clearer, a hand, an arm, a shoulder, the particular face. The mouth opens and the voice comes clear and sure and strong. It says, I want to go home to my family; it says, you know, when I was five years old, my father burnt me, I’ve been thinking about that lately; it says, I really want to travel, I want to get my GED, I want to write to my kid and explain. “They said you should tell the truth,” Aush tells me, and laughs. “But they said be gentle.”

Pete asks for Steve. Turns out he knows Steve from Green Haven. First time Pete saw him was back in ’82 when Steve was in “semi-ice,” right after a 21-month stint in the Box. Pete was the only general-population prisoner allowed into the unit because he was a porter and he went in there to sweep. He noticed Steve because Steve is white and white guys look for each other inside, and he noticed Steve because “he was looking at me like he wanted to tear my head off.” Pete asked around and heard that Steve was all right, like really all right. Pete approached him slowly—a few words, a cigarette, then he started bringing food up to Steve. That’s when Steve told Pete he had AIDS. Pete brought the food in his own dish and Steve thought he should know who was eating out of his plate. “He took a big chance,” Pete says. “I could’ve told everyone.” · We talk about Steve for a while and then Pete leaves. His head seems to move by itself, unconnected to the floor; the body, wavering and thin, an afterthought. The will to live, the scheming, the fighting, the wishing pull the body after it, through the door and down the hallway—the feet confused, cloudy on the floor. “Pete’s got us all scared,” Michael says. “He can’t keep any food down. At night, when I’m in my bathroom reading, I can hear him in his bathroom throwing up.”

I ask Officer Brown why it is that all the men seem scared of going to the hospital, any hospital not just Goldwater. “The corrections officers at the hospital are not as sensitive to them as we are,” Brown says. “They’re handcuffed to their beds, the officers are scared of them-psychologically, that does damage to them. I’ve seen them come back in here bony, frail, scared, wide-eyed. …” Going to the hospital is like going to jail, Brown says. No TV, no microwave, no cereal in the kitchen cabinet. Just lying in bed, strung up on an IV and shackled down, “thinking all day long.” Brown says after a day or so back in the dorm, they’re walking and kidding around. “It’s a psychological thing.”

When I visited Ignacio at the prison ward of Kings County hospital, he said he had spent one day and a night in receiving, handcuffed to a stretcher most of the time. In the ward, one of the officers was talking at Ignacio as if he were dirt and Ignacio had to pull rank—“I respect you, you should respect me. I’m older than you.” Ignacio holds the officer in complete contempt. “He’d probably put his own mother in jail.”

Ignacio, senior man, “the strong voice of the dorm,” as one officer called him, is losing his voice. Doctors suspect throat cancer but Ignacio has refused a biopsy. He doesn’t want to have to breathe through a flapping hole in his throat. He’s afraid he won’t recover.

There are two Ignacios. Ignacio is vigorous, devious, flirtatious, sociable, a con man. The tattoos are there still; the sloping, gleaming belly. Then Ignacio’s shuffling through the door, feet scrape-scrape flat across the floor, his face is fleshless, he rasps. Still the eyes are wicked-warm and I know Ignacio is going to make sure we have fun. He says if he dies tomorrow, he’ll die happy. He’s lived more than most men. That’s an incredible thing to say, I say, if I died tomorrow I wouldn’t be happy. “How could you be happy? You’d be dead!” And Ignacio I is laughing heartily and Ignacio II is making no sound.

There are days now when Ignacio can walk normally again. He’s not a man inclined to rapture but he feels “like a baby when it takes its first steps.” Not a man inclined to illusions. When I tell him I saw Steve in Downstate Prison and he looks great—strong, big—Ignacio’s eyes gleam. He’s seen Steve leave Dorm 4 looking like that. “And I’ve seen him come back like this,” And Ignacio holds one pinky finger in the air.

He tells me “Eduardo” is also in the hospital. Eduardo is known for a unique talent-he can bark exactly, I mean exactly, like a dog. One afternoon, I was talking with Michael and Ignacio in Dorm 4 and suddenly, yap-yap-yap! I jerked around in my chair, looking, and the men all laughed. It’s hard to explain the effect of that sound in that kind of place. All those locked doors and clicking corridors and even light, all that steel, all that procedure, and a dog got in! Sharp yapping, boisterous … a living, wagging, bounding dog. What the hell? How the–? I’m told there’s a guy in one of the maximum security prisons who can cry exactly like a baby.

Ignacio tells me that Eduardo tried barking in the hospital prison ward and a guard told him, “You do that one more time and I’ll write you up 10 tickets.” So the men hate going to the hospital-not just because they’re handcuffed to the bed, surrounded by people who are afraid of them, but because of the stupid, humorless repression. There will be no fun, do you hear me? NO FUN in the hospital prison ward.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When Ringler arrived at Dorm 4, he was skinny, old, and shitting on himself. He came with nothing-no money, no apparent family. And he was a cigarette fiend. Always asking, always dirtying himself. Just rude, smelly, and frightening. “And nobody wanted to be close to him, nobody wanted to help him, nobody wanted to give him cigarettes,” Michael remembers. “Except one person, and that person was Steve.” That’s how it always happens Michael tells me—“No matter how spiteful, how hateful a person may be, there’s always one person in here that gets along with him and he’s gonna go and try to help him.”

And Steve tried to win Michael over to the old guy’s side: “Hey, Michael—this guy, he’s sick, yeah, he’s a little off, but he’s all right. He knows what he’s doing, it’s just that he can’t control it.”

Michael says, “Me and Steve used to do our shopping together. And we always used to buy something extra to give to the guy. We wouldn’t give it to him all at once because he would eat it and or drink it right away. It won’t last him. So we used to give it to him in portions.”

They moved the old man into semi-ice and Steve found him clean pajamas. “People started catching on-doing the same thing, trying to help him out, helping him stay clean. Just caring a little more,” says Michael. “And people started liking him and everything.” The men began calling him Pop or Mister Ringler. “He started seeing people caring. He wanted to change now. He wanted to be clean. He wanted to impress somebody. He felt like he was somebody, there was some kind of importance for him to be in this world, you know? And that maybe somebody will remember him when he dies.”

When I look back at my notes, I realize how little Michael talked about himself the night solitude, the missed career, his brother’s reluctant embrace. When he spoke of the other inmates’ fears (of losing good officers, of dying) Michael would sometimes add at the end, “Even me. …” Even he was afraid.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

At the end of July, tensions are high in Dorm 4. Brown is on vacation and the inmates know that soon after he comes back, he’ll be transferring to Goldwater Hospital, escaping the heavy bureaucracy of Rikers and his constant battle against regulations not designed for sick men. Only very experienced officers are posted to Goldwater because they work without onsite supervision. The teaching contract was awarded to another agency, and Aush is waiting to see if she gets the job. She hasn’t been to the dorm in a month and they miss her. “Mike, Mike, why don’t you write a few letters?”’ the guys ask him. “They depended on her to come every morning and teach them,” Michael says. “Some people from DOC have the attitude like “Why are you teaching these guys GED—they’re dying. They can’t put it to any good cause.’ If you’re not doing anything, you feel like you’re dying, like everybody gave up on you. If everybody gives up on you, why fight?” Mr. Ringler, Pop, is gone to Goldwater. Ignacio, the senior man, is long gone to Kings County. Guillermo is dead.

“I gotta tell you a story about this place,” Steve says. We are sitting in the visiting room in Downstate Correctional, where prisoners get processed before being farmed out to state facilities. Where the bad boys from Rikers, with their skittery, premature violence, their petty grudges that show up as razor scars on someone’s face, get stomped. “This is like bootcamp. It’s very strict. They try to intimidate you. And it works with the kids, you know. People like me—it doesn’t work-because I know it’s all bullshit. The reason they do it is these people come from Rikers Island and it has a kind of wild reputation and they want you to know that now-NOW- you’re gonna get punishment.” Steve calls Rikers “a kiddie joint.”

Steve in Dorm 4 was polite, smiling, helpful, and somewhat strained, like we had been forced to go through a party sober. He gave me a tour of the place, showing me the microwave oven, the isolation units, opening every cabinet in the dayroom to show me the food inside. It was the place that he built, but I saw none of the pride, the possessiveness that day. He could’ve been the gardener.

We were standing by the one-man isolation units when a guy came flapping and hollering down the hall. This place is making me sick! he shouted, I was fine until I came here! He wanted out. Steve broke in quickly, firmly, telling me the guy was sent here straight from the hospital, straight from a bout of PCP. Some people want to blame the disease on something else, Steve said, while the guy hung there in the air. Midflap.

Less than a week later, Steve was moved out. He wrote me from Downstate, clearing – the way for our relationship: “Take heed, – I’m not some soft kid who got a bad break in life, most of the punishment I have received in life, I so richly deserved.” Steve in Downstate was a shock. His head was shaved, giving him the look of a bully or a victim, kind of loony tunes and dangerous. He lowered his head and glared, demonstrating his “best look of hate.” Kind of a show-off. But what was striking was his confidence. At ease, and charged. Like it all came together here. In a fucking cage. “I gotta tell you a story about this place. To let you know the kind of people they have here. It’s a whole different thing than they have at Rikers.

“In ’86 when I came in here for parole violation, they transferred me with ‘José Gonzalez.’ A kid. And this kid was just diagnosed and was really scared. And he was crying. He was fucked up, you know? This is my only failure. He’s my failure, right? Because usually I can turn somebody around.” Steve and José were put into a two-man isolation unit in the infirmary and Steve started to work on José, to get him to toughen up. “Now’s the time,” he told José. “You can always drop dead.” But it just wouldn’t take. “I was watching his mother and his girl come up and they would leave in tears and I used to tell him, “There’s nothing they can do for you. Nothing. Not a fucking thing. They can’t help you, they can’t get you released, they can’t do anything. So go out and tell them you feel okay, even if you don’t. Why have them leave here crying?’ ” But José couldn’t cut himself loose from the panic, and after three weeks Steve couldn’t take it anymore.

He asked out. There’s no place to put you, the staff said. “Put me with Olivera.” Steve knew Angel Olivera from the Third Floor—they had gone through a couple of hunger strikes together. “I liked him a lot. He was in a back room and he was dying.” You don’t want to go in there, they said. But Steve did.

When they opened the door, Steve could smell the shit. “And here’s this fucking guy who’s laying in this fucking bed. Nobody changed him. He wasn’t eating so they were just stacking meals up on this hospital table. His sheets were soiled, diapers were soiled. He was just laying there … the guy was fucking crying.” .

Steve asked them to leave the door open for a while because you’re locked into isolation units and locked tight. He was gonna clean up. The nurses looked at him—You? Gonna do what? They knew Steve and they knew him as hardcore. “I put some gloves on. I put on one of them yellow smocks that I fought with the police not to wear and I cleaned this motherfucker up. (I call him a motherfucker but he’s my friend.) Changed his diapers, put him in the shower, changed his sheets, everything. While I was doing this, they were watching me, peeking at me. I shamed those motherfuckers.”

He has been punished and punished well. Now he’s a man who says: “There’s only so much they can do to you, you know. They can’t eat you.” And grins when he says it. In ’82, Steve was imprisoned in Green Havén. He was working on the farm when his mouth and throat began to fill up with thrush, and his bowels turned to water. He’d been shooting up and sharing needles inside, but Steve’s been shooting up since he was 15 when the needle and strap looked cool, so he could’ve caught the virus anywhere. Steve was sick, real sick, and he panicked. He escaped from Green Haven, and they caught him and brought him back and punished him good. All in all, in 1983 and ’84, Steve did 21 months in the Box.

He was taken out of the Box in August of °83 and brought to Westchester Medical Center with PCP and cryptosporidiosis diarrhea. He was almost dead. Steve remembers the medical staff yelling, “Put a line in him! Put a line in! What the hell are they doing over there?” When Steve was returned to the prison infirmary, he was locked in isolation. A bucket of bleach for a toilet, and no running water. A Box with a Window and other inmates used to crowd around to get a look-He’s got the shit! He’s gonna die!

He was allowed out for a shower only when he was well enough to clean and disinfect it himself afterward. Steve doesn’t like to admit this, it shames him, but he began to think about suicide then. That option was a piece of control. But when the guards began to suggest exactly that—why don’t you just kill yourself and get it over with?-Steve figured he’d live just for spite. “There came a time in that situation where something just clicked in my head out of anger, out of just f-fucking rage …” He watched how the officers abused the sick prisoners in the infirmary. Freddy had a rash so bad, so sticky, he couldn’t pull a pair of pants on. “When it came time to take him to the hospital, they used to dress up in all this outrageous shit. And everybody would threaten the fucking kid—this kid that was on his deathbed— If you spit at me, I’ll kill you, I’ll blow your brains out, you piece of shit.’” When they started with Steve, he said, “You know what? I’m ready

to go right today but I’m gonna take you fucking with me. You’re gonna kill me and my teeth are gonna be sunk in your fucking neck.” So they came in groups to feed him, they wore masks and helmets and pushed his tray in with a stick. “It was almost like I had a gun, you know? Back then, they didn’t know. They didn’t know if I touched somebody, were they gonna get it? And I dug on that, you know? I dug on that power. I’m not gonna lie to you. It was like a fucking power. Believe me, I was in control of that six-feet-by-eight-feet. No one would come in and I was in control of that. And that’s all I had.”

For a few years now, doctors have been predicting Steve’s remaining life span and finding it “certainly grim by all standards given his long-standing AIDS.” Steve sees it differently. “This is gonna sound like flying saucers but right now I’m probably the longest-living, strongest AIDS victim in the fucking world. It’s a fact. I got this beat.”. He says that since 1983, he’s thought, “If it’s possible that anybody could beat this disease, then the right person’s got it.” And he’s been going on that thought ever since.

In person, Steve will say, “They got all these guys in here and they’re all apples, you know, and then they’ve got a fucking watermelon.” He’ll grin at the wall behind your head until you’re itching to turn around. He knows how to keep you on edge. His letters aren’t funny or pissed. They’re written on a grander scale—“I watched how you struggled with some very alien concepts of mine, also the pain in your eyes as I related another’s battle with death, this makes you worthy of my guided tour,” he writes. No grinning at the wall. If he wants to do that he draws a smiley face on the page. Writing makes him nervous. It’s not like talking, where you can use the tone of your voice, says the man who can clip a dumb word like “nice” and make it burn. He’s afraid his writing will sound “infantile.”

He closes one letter: “Help me to bring back what has come to pass, what everyone else pretends never happened and what I will never forget, but waste not one tear of pity for me, for I have lived with GIANTS and now there’s no nobody left at home, in this house of pain.”

In January of ’86, Steve was transferred from Bellevue hospital to the Third Floor of Rikers Island. He remembers it was nighttime. He remembers the transporting cops wearing masks and gloves, and that he, too, was forced to wear a mask. He remembers arriving at Rikers and the officer telling him, “You don’t have to wear that mask anymore.” He was brought to the Third Floor. The tier was dark. A TV flickered black and white. No one was watching. No one could be seen anywhere. Steve thought, “Where the fuck is everybody? This isn’t the jails I know-everybody screaming and …” The officer on duty told him to pick a cell and he headed toward the last one. “And on my way to the back, I was looking in the cells,” Steve remembers, “And I seen these guys—all stick men, except for maybe one or two guys, all coughing, all just like, really. like …,” Steve smiles. “… Miserable looking motherfuckers.”

“These guys were very, very depressed. Most of them wouldn’t come out of their cells,” Steve remembers. They were being sent on their visits with AIDS printed on their slippers, officers didn’t want to take them to court or to the yard. They were walled off from the world.

When Steve started working out in his cell, the guys looked at him as if he had dropped from another planet. One-Two-Three-Four. They watched and after a while some of the guys started to do pushups in the morning too. The ones who could. One-Two. Most of that first generation were too far gone, diagnosed late, diagnosed wrong, already in the last stages of the disease. The officers did what they could-giving them extra food. “They were starving,” Brown says.

According to Steve, things changed when some new men arrived. They were not all stick men. They were older guys who had done a lot of time-a breed of men that Officer Brown and Steve call “dinosaurs” – men who didn’t think of themselves as victims of the system, or as innocent, and so were less likely to sink into depression and inaction. But it was the slow death of Pablo Ruiz that set off the first strike. “They sent him to the hospital three times and the hospital kept sending him back,” Steve remembers. There was nothing a hospital could do for Ruiz. He was dying. He had lymphoma and back-to-back-to-back pneumonias. “But the thing is they thought they were sending him back to another hospital – Rikers Island hospital. And they didn’t know these people were going back to a cell with paper sheets, filthy, dirty, mice and roaches, and they weren’t receiving any pain medication.” Two men had just died when they brought Ruiz back onto the Third Floor, pushing him in a wheelchair.

“Are you all right, man?!” Steve asked Ruiz. “I’m through, Stevie, I’m through.” “Nah, nah, we’re gonna hook you up, man, you’ll be okay,” Steve told Ruiz, trying to talk some life into him. “There’s nothing you can do,” Ruiz said.

“Then a few hours before they took him out again, he tells me, ‘Fuck this, man, just fuckin’ ice me.’” Smother me with a pillow, Stevie. And Stevie stood there deciding, should he or shouldn’t he? “I mean I had to think about it! I was all fucked up and I left the cell and I’m saying, “What am I even thinking about? What the fuck is going on here? This is 1986—what the fuck is going on?”

They brought Ruiz out again (he died a few days later), Steve said fuck it—and he got the guys to agree to a hunger strike. “And I had a guy named Tony who’s since dead. A son of a Mafia I call him. His family was all Mafia. I guess that was their punishment. The guy used to sell cars for a living, you know? So he was fast, good, quick. And he got on the phone and started talking to all these people.” Newsday came out a few days later and reported the story. “Once we got publicity, I knew it was gonna work,” Steve says.

They got extra food and real sheets. Not much but they saw they could do it. “Then a guy named Peter Arroya, who’s long dead, came down from Sing Sing and he kind of souped up the second strike.” They wanted a microwave, extra food, nutritional drinks, pain medication. They wanted a name for the Third Floor like Special Needs Unit so they wouldn’t be labeled everytime they went to court or on visits. They wanted AIDS taken off their slippers. “We were trying to set some kind of precedent.”

“And you did.” “Oh, yeah, we did.”

An inmate in Dorm 4 once made the | mistake of saying to Steve, “It couldn’t have been that different then.” Aush remembers: “(Steve) exploded. I saw a side of him I hadn’t seen before. When he loses control, it’s scary.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Out of all the men Steve’s known who fought hard and are now dead, one stands out and away from the rest: Nick Nikura, the daddy of dinosaurs. “I liked this guy right away,” Steve says. When Nick arrived on the Third Floor, Steve was sitting outside his cell at a little table where he had a long-shot view of the tier. Here comes another miserable …, carrying his paper sheets under his arm, picking out his cell. His shirt is off and his back and chest are covered with sores. There’s no hair on his head, there’s scales. Holy shit. The guys are looking at him “in like, terror,” Steve says. “Because they were thinking, ‘Is this gonna happen to me?’ ” Nick keeps walking. All eyes follow him in awe. And then Nick, looking straight ahead and at none of them, begins to laugh. Low, then louder.

“Heh-heh-heh. Heh-heh-heh.” Officer Brown is imitating Nick’s laugh. “I hear that laugh now. He was a piece of work that boy was. Oh, yeah. Nick.”

Whenever guys in Dorm 4 complain that I they’re in too much pain to do anything but take to their beds, Brown says, “You talk about pain? You don’t know what pain is.” And then Brown tells them the story of Nick. “That boy was in so much pain that he just made the hair stand up on my arm. He would be struggling to get out of bed ’cause he didn’t want anybody to help him and his whole face would be red, his head would be red, he had a Kojak-looking head and it would be red. He had to walk like”— Brown grabs ahold of the desk, paws the walls, bites down—“just to go to the bathroom and back to his bed. His leg was just like petrified wood, trying to be a part of his body. And all that pain was just going through his body. One day he’d be up and at ’em, and the next day, he just be down and low.”

I met Nick at the very end, lying in a fetal curl in the last bed in Dorm 18, facing the wall. It was 1988, the Association for Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment was working with the inmates then, and director Yolanda Serrano brought me into the dorm. Nick was skeletal, shedding skin, and Yolanda found one spot on his hand free from sores and held Nick there. She asked if he was in pain and Nick said. “No. they’ve taken care of that. It’s the fevers and the vomiting …” And then he started to shake with coughing or laughter. I didn’t know which one then.

Nick didn’t want his mother to visit him, even though Yolanda could get her in. Steve explains-you do your time alone, you don’t put your family through the travel, the long wait, the degrading searches. And Nick’s mother was 80-something years old. Officer Brown says, “Some of these guys, the older ones, know what they’re up against and they want to do it gracefully. They don’t want to see the tears in their children’s or their loved one’s eyes. The less physical contact, the less eye contact, the better off …” They feel they’ve hurt their families with their addiction, their crime, their incarceration. For some of the men, the guilt and the shame are overwhelming. It’s too much and much too late to make amends now. Once Steve said simply that Nick wanted to die with people that cared about him: Men who understood him and not with a mother’s piteous, bewildered love. When they took Nick out for the last time, he called Steve from the hospital and promised, “Somehow, I’ll let you know if the devil really does have horns.” It’s not something a mother would appreciate.

“I miss Nick, man,” Brown says, standing in the guard station at Dorm 4. “He used to come to the window and talk about explosives and army tactics and we’d exchange books and talk about weapons-and he came alive! I was on pass for two or three days and when I come back, Nick isn’t here. When he died, a piece of me

died. One in fifty of ’em get to me, you know? When he passed, I was ready to quit the whole business.” Brown laughs, a short and sad sound. “I was just, ‘Nah, I can’t take this, I’m going to general population where I don’t have to deal with this no more.’” Brown is close to tears.

In September, Brown’s gone from Dorm 4, taking the magic tape with him. Aush doesn’t get the teaching job—an older woman comes into the dorm now and plies the men with candy to get them to come to class. Many of the officers who leave don’t tell their fellow officers that they once worked in the AIDS dorm because of the prejudice. But they come back to visit the men often.

After months of legal maneuvering, Shorty finally won his Compassionate Release. Last I heard, Pete the Barber was still alive in Goldwater. Through one of the officers, I hear that the D.A. offered Michael four to eight years—a sentence longer than his life expectancy—and he has sunk into depression.

In a letter, Steve writes “I remember Louis Simmons, Billy Camacho, Victor Camacho, Albert Sweet, Joe Hauser, Juan Morales, Carl Jacobs, Paul Colgan, Robert Spain, Bruce Olum, Eric Parker, Pete Arroyo, John DePaulo …” Just their names. A long list in pencil on a sheet of legal paper.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~